Toronto 1837: A Model City

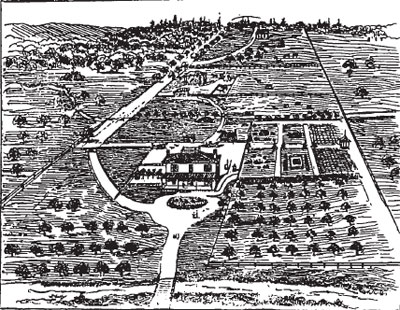

This scale model of Toronto in 1837 is located in the Town of York Historical Society’s museum at Toronto’s First Post

Scale Model of Toronto, 1837

We remain grateful to the many individuals who helped finance the model by purchasing individual properties, and to the various young people who researched and described the major features of the nascent city of Toronto. Their work brings early Toronto to vivid life and adds immeasurably to understanding today’s

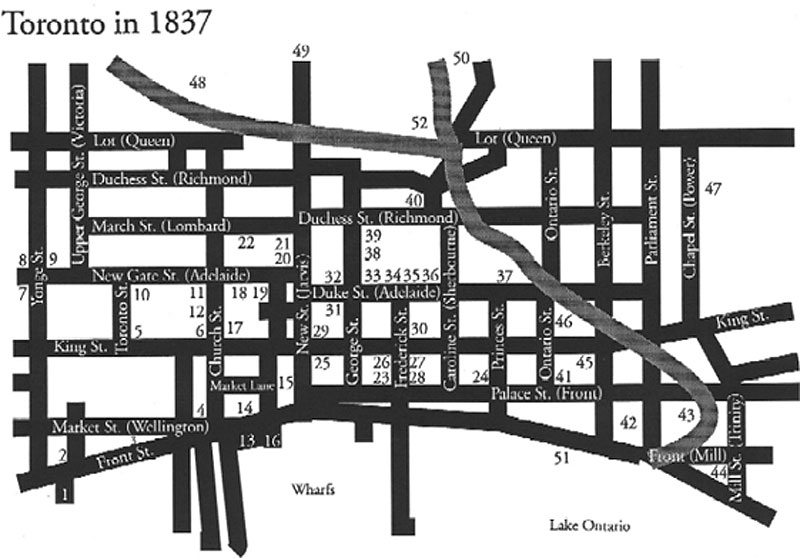

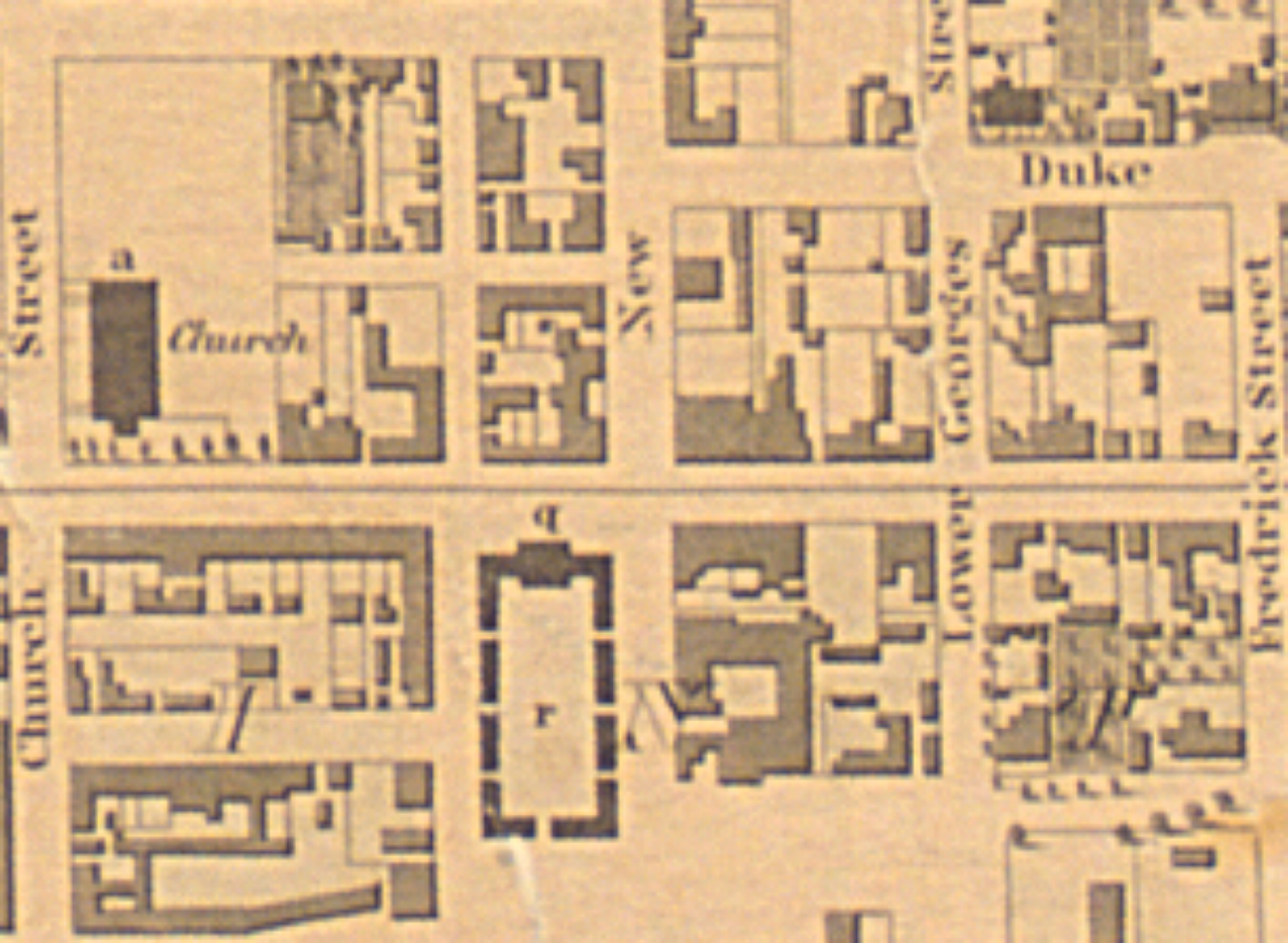

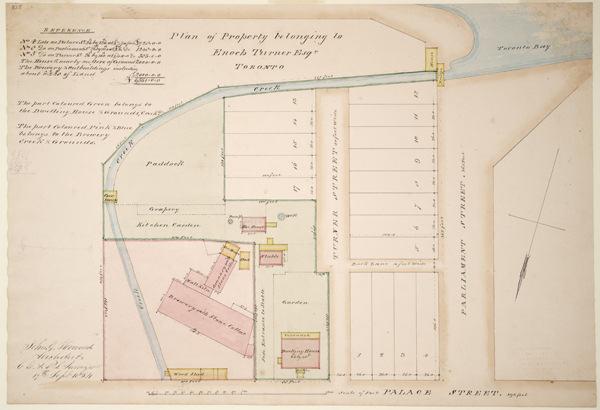

Toronto in 1837, Model Map.

Explore Toronto in 1837 by clicking on each number below:

1. Freeland’s Soap and Candle Factory

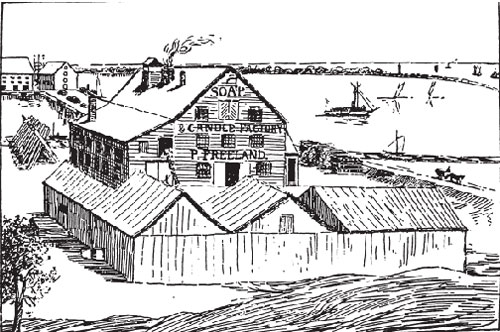

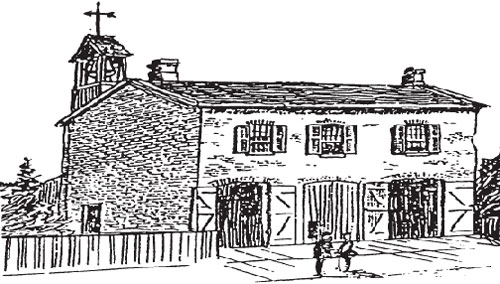

Freeland’s Soap and Candle Factory

The York industries of lather and light had their origins in Peter Freeland (d.1861), a Glasgow-born Scot who crossed the Atlantic in 1819(1). After first starting a soap and candle factory with his brother William in Montreal, Peter then came to York in 1832 to found his own company(2). He purchased a water lot at the foot of Yonge Street from Judge Levius P. Sherwood, and Peter MacDougall(3). This resulted in his dynamic entrance onto the commercial scene of York, and the establishment of what was for some time a major landmark along the waterfront.

As most of the property was submerged, the rear warehouses of Freeland’s Soap and Candle Factory were supported by large piers. The high water level allowed schooners carrying goods to dock and unload directly. Iron soap-kettles were brought from Scotland(4). Candle

The factory consisted of a series of sheds, as seen in the above picture, which stored ingredients such as tallow, palm oil, wood ashes, lime and ice(6). Inside, the workmen would hand-cut and shape the candles and bars of soap.

Due to Freeland’s careful methods, what could have been a fire hazard remained a safe and viable industry for many years.

Notes

1 John R. Robertson, Landmarks of Toronto, Vol. I (Toronto: J.R. Robertson, 1894), p.186.

2 Edith G. Firth, The Town of York 1815-1834, Ontario Series Vol. VIII (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966), p.70.

3 Robertson, I, p.182.

4 Lucy B. Martyn, Original Toronto, (Sutton West: Paget Press, 1983), p.67.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Robertson, I, p.183.

8 Ibid.

9 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.67.

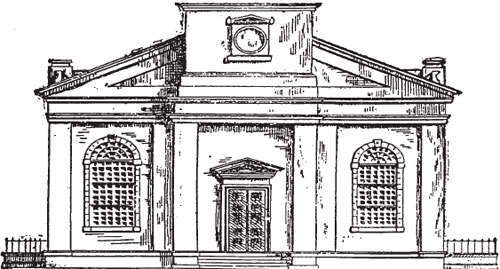

2. Customs House

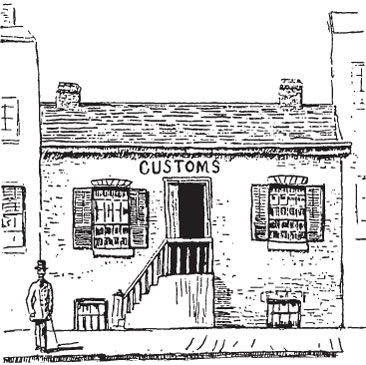

Customs House

York was made a port of customs in 1801(1). At the time of our model Toronto’s second, or York’s fifth, Custom House (1835-1841) was in operation. It was located on the north side of Palace (now Front) Street, within the first block east of Yonge. A single-storey brick structure, the Custom House was hip-roofed as many of the other buildings of its class(2).

The busy harbour of early Toronto was the scene of many problems caused principally by smuggling networks operating between America and Toronto. The official responsible for monitoring this illegal activity was the Collector of Customs. The Collector would confiscate all smuggled stock, whether found on board ship or in town, within a maximum period of three years from entry(3). Tea and fish oils, prohibited by imperial statute, were among the most frequently confiscated goods(4). A monopoly of the East India Company and legally sold in Quebec, tea created the greatest problem: an estimated 3000 chests of it arrived illegally in Toronto each year(5).

Thomas Carfrae, Jr. (1796-1841) of Edinburgh, Scotland was the Collector of Customs in 1837(6). He rose to civic prominence in 1826 as one of the founders of York’s non-sectarian burial ground, know as “Potter’s Field” or the York General Burying Ground(7). However Carfrae had a broad portfolio, ranging from politics to forming York’s first Fire Department [site 12](8). Following his post as Collector of Customs, Carfrae was appointed Harbour Master in 1838(9).

The office of Collector of Customs was created to protect York markets and industries from the in of illegal products which might have harmed their fledgling economy. The Collector also monitored the flow of human traffic, for example deserters heading south. It was a unique and prestigious appointment, which also proved to be financially profitable for those who held it.

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.251.

2 Ibid., p.255.

3 Frederick H. Armstrong, A City in the Making, (Toronto: Dundurn Press Ltd., 1988), p.185.

4 Ibid., p.184.

5 Ibid.

6 Firth, p.103.

7 Roberston, I, p.253.

8 Armstrong, A City in the Making, p.169.

9 Firth, p.103

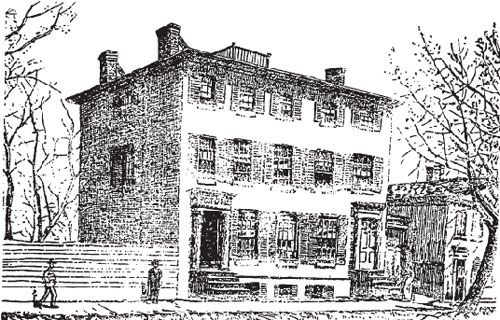

3. The Coffin Block

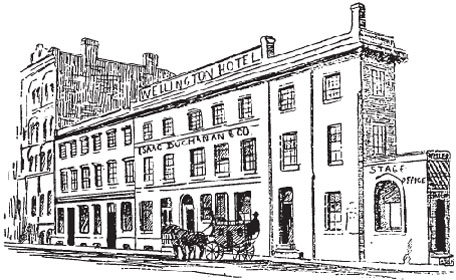

The Coffin Block

Built on the converging point of Palace (now Front) and Market (now Wellington) Streets was the unique building attributed to architect John Ewart (1788-1867)(1). This simple, circa 1830s, yellow-painted (or possibly stucco) brick structure reminded local people of an early coffin because of its tapered shape(2). Affectionately dubbed the “coffin block”, its distinctive shape made it the local landmark of the day.

The coffin block housed a series of different commercial establishments. It was divided into three units, the smallest of which was located right at the intersection(3). This space was best known as the booking office of William Weller’s stagecoach lines from 1830-1835(4). Weller offered stages to areas east and west of York, and later Toronto, the principal route running between York and Hamilton(5). Generally, due to poor road conditions, it was only considered safe to travel in the winter(6). Weller’s Toronto-Montreal trip of 35 hours and 40 minutes remained a record until the prominence of rail travel(7).

At the time of the 1837 Rebellion, Isaac Buchanan and Company’s Wholesale Warehouse occupied the main part of the building(8). Officers’ quarters were located on the upper floors, the confectioner James Scott was on the main floor and Bannerman’s restaurant was in the basement(9). All of which flourished under the patronage of the militia.

Located close to the wharfs, and the centre of stagecoach travel, the coffin block figured as a natural point of reference for many early travellers to Toronto. This was further confirmed in the 1840s when the Wellington Hotel converted the two upper floors of the coffin block into an annex(10). Ewart’s coffin block was demolished in 1891 so that Gooderham and Worts [site 44] could construct the “flatiron” building which stands in its place today(11).

Notes

1 Martyn, The Face of Early Toronto, p.37.

2 Ibid.

3 William Dendy, Lost Toronto, (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1978), p.53.

4 Robertson, I, p.380.

5 Ibid., p.223.

6 Edward C. Guillet, Pioneer Inns and Taverns, Vol. I (published by the author, 1954), pp.31-2.

7 Ibid.

8 Robertson, I, p.380.

9 Ibid., pp.380-4.

10 Dendy, Lost Toronto, p.53.

11 Ibid.

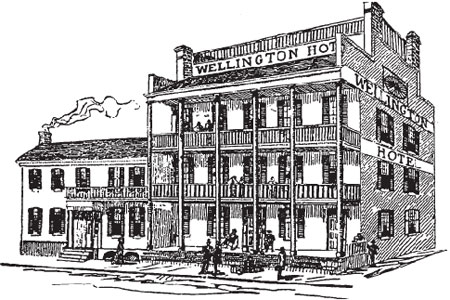

4. The Ontario House Hotel

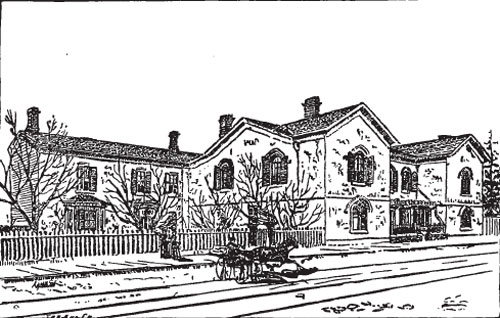

The Ontario House Hotel

The Ontario House Hotel of the late 1830s was impressive in both location and design. Situated on the northwest corner of Market (now Wellington) and Church Streets, it offered visitors a wonderful view of the

From domestic to commercial, the home emerged as the Ontario House Hotel in 1829 through the efforts of John Brown(3). Brown, a Niagara Falls hotelkeeper, then sold the hotel to David Botsford in 1830(4). The hotel changed hands several times throughout the years 1830-1845, with one of the more prominent landlords being William Campbell [site 36].

The Ontario House Hotel was the grand hotel of early Toronto. Its location was ideal for the

Like today another role of the hotel was to serve the community as a meeting place and public venue. For instance, during the election riot of 1841, Reformers began their victory procession from Ontario House(6). In 1845 the Ontario House Hotel became the Wellington Hotel, under the ownership of Russel Inglis who later rented the two upper

The early hotels of Toronto, whether in name, custom or legend, are

Notes

1 Firth, p.72.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid., p.86.

4 Ibid.

5 Guillet, p.78.

6 Ibid., p.79.

7 Ibid., p.81.

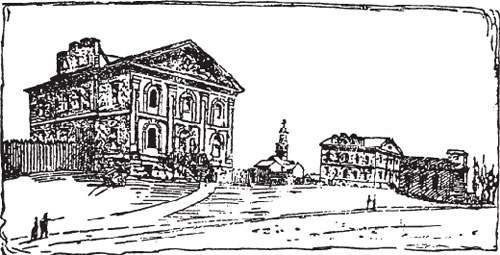

5. & 6. The Courthouse and the Jail

The Courthouse and the Jail

The Court of the Quarter Sessions of the Home District served as the governing body of York. It consisted of local merchants (largely Scottish) who were appointed to the post of

The price tag for the

The

Inside, the prisoner’s box was placed on wheels so that it could be moved into a corner out of the way when the large room was used for public affairs. In order to save money in the soon over-budget venture, sacrifices were made in construction. For example, walls were built slightly thinner than originally designed, which proved to be the downfall of the jail as it made for easy escape routes(7).

Lieutenant-Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland laid the cornerstones of both buildings on April 24, 1824(8). In the tradition of time-capsules, a sovereign, a

Notes

1 Armstrong, A City in the Making, p.165.

2 Firth, p.261.

3 Ibid., p.263.

4 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.45.

5 Martyn, The Face of Early Toronto, p.55.

6 Ibid.

7 Marion MacRae and Anthony Adamson,

8 Martyn, The Face of Early Toronto, p.55.

9 Robertson, I, p.85.

10 Armstrong, A City in the Making, p.42.

11 Firth, p.lxxxii.

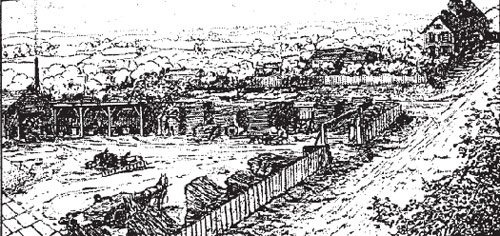

7. Jesse Ketchum’s Tannery

Jesse Ketchum’s Tannery

Ketchum brothers were Americans of Welsh descent from Spencertown, New York. They were members of a large family which had intermarried with the presidential Adams family of Massachusetts(1). Seneca Ketchum (1772-1850), the eldest, moved to York in 1796 to earn his fortune(2). Jesse (1782-1867), the second son, was placed on a farm in New York State from which he promptly ran away from in order to join his brother(3). When Jesse met up with Seneca in York, he discovered that his brother had indeed become a success. Seneca was a landowner and the proprietor of a tannery, of which Jesse later assisted in managing.

On the eve of the War of 1812, an American named Van Zandt sold his property on the southwest corner of Yonge and Lot (now Queen) Streets to Jesse Ketchum(4). There, on the southwestern corner of Yonge and Newgate (now Adelaide), Ketchum opened his tannery. The structures required by Ketchum demanded an enormous amount of space, and as a

As described by John R. Robertson in his Landmarks of Toronto, Volume 1, 1894 edition, the tannery consisted of a chain of sheds. There were rows of deep vats, mounds of leather tan, and hemlock bark which, at times, became a makeshift playground for children. A horse-powered mill ground the bark for processing. The entire scene was intensified by the smell emanating from the piles of hides waiting to be cured on the currier’s blocks.

Ketchum’s tannery was one of the most extensive and lucrative industries in York. He complemented this commercial success with acts of humanitarianism. For example, whenever an employee married, Ketchum generally gave the newlyweds land for a home, and sometimes the financial support for its construction(6). Ketchum’s benevolence also extended to the religious and educational communities of York and early Toronto [site 8].

A true success story, J

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.32.

2 Firth, p.66.

3 Ibid.

4 Robertson, I, p.33.

5 Ibid., p.31.

6 Ibid., p.32.

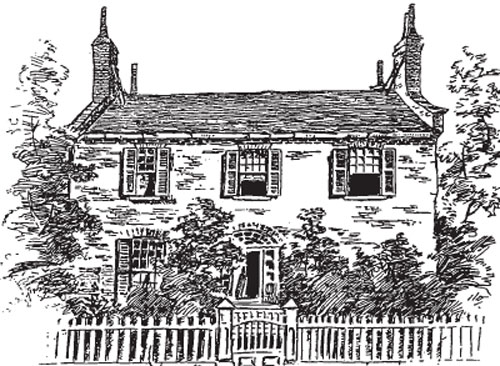

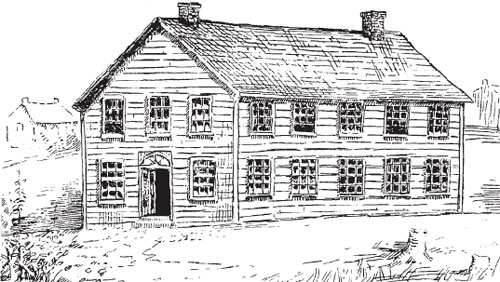

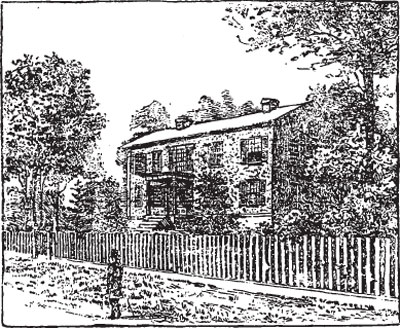

8. The Ketchum Family Home

The Ketchum Family Home

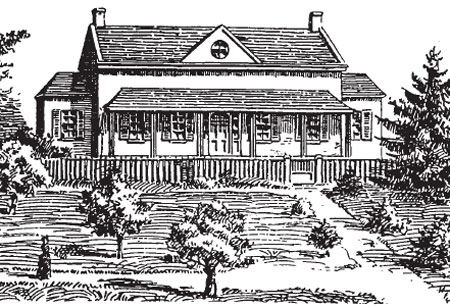

Built circa 1813, the Ketchum home was designed in the style of American Architecture(1). It was a large building, painted white, with a flat, square turret that sprouted from the roof(2). In the tradition of the early merchants of York, Ketchum chose to live near his business. His home was located directly across the street from the tannery [site 7], on the northwest corner of Yonge and Newgate (now Adelaide) Streets(3).

One of the most prominent citizens in York, and a leading benefactor, Jesse Ketchum undertook no project which did not better the community in some way. For example, at the Ketchum

Ketchum’s house was demolished in 1839, and the land was divided into smaller lots(5). However his legacy was carried on through his many other contributions to the town of York, and later Toronto. For instance, the concentration of churches and schools on what was his land, bordered by Lot (now Queen), Newgate, Yonge

Not without his own hardships, Jesse Ketchum was the son of an alcoholic father(7). He founded Temperance Street in 1837, stipulating that no liquor could be sold in any building which fronted onto the street(8).

When Jesse Ketchum left Toronto in 1845 to return to Buffalo, he was esteemed as a humanitarian, a pew holder, a successful businessman, a reformer and a friend to all children(9).

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.31.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.35.

6 Robertson, I, p.31.

7 Mike Filey, Toronto Sketches “The Way We Were”, (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1992), p.2.

8 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.35.

9 Robertson, I, p.30.

9. The Sheldon, Dutcher and Company Foundry

The Sheldon, Dutcher and Company Foundry

The growing 1830s economy of York cultivated an environment of industrial expansion, particularly along the southern end of Yonge Street. The Ketchum Tannery [site 7]; Peter Freeland’s Soap and Candle Factory [site 1], and York’s two manufacturers of Steam Engines were all contemporary to this period. Together they served as supporting evidence to the town’s increasing population, the strength of their market economy and technological maturity.

Frederick R. Dutcher, an early commercial investor, had moved his foundry from Dundas Street to York, near the northeast corner of Newgate (now Adelaide) and Yonge, in February 1828(1). He partnered himself with a variety of local businessmen at different times including William B. Sheldon, Samuel Andress and J. and V. Norman(2).

The firm went out of business sometime between 1836 and 1843. Prior to its

At its

Notes

1 Firth, p.60.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid., pp.60, 81.

4 Ibid., p.60.

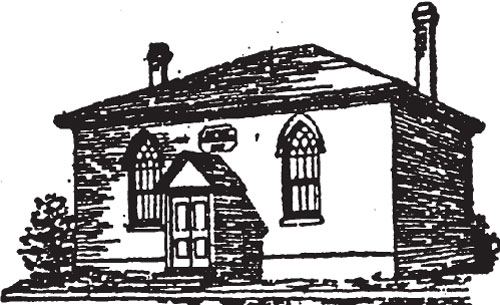

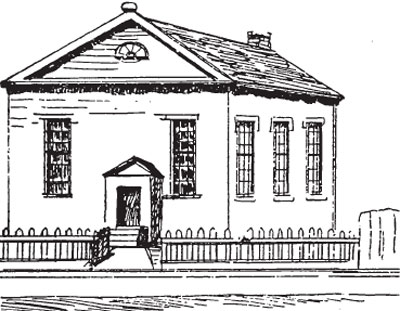

10. The Methodist Church

The Methodist Church

Methodism came to Canada on horseback. American ministers, once trained, would ride along a circuit of scattered farming settlements, bringing with them lessons on religion and education(1). They spoke fervently in all types of settings from barns to makeshift meetinghouses.

Through the efforts of Robert Petch, Methodism came to York in 1818 in the form of a small wooden church on the southwest corner of King and Jordan Streets(2). It was a perfect example of the Methodist preference for the Greek temple shape (a long rectangular block with pedimented gable ends at the main entrance)(3).

The fledgling congregation met with many challenges in early York. Politically, British settlers were suspicious of the American Methodist ministers who might have been tempted to preach the virtues of Republicanism. In the midst of this the Canadian Methodists attempted to find their voice in what was already a foreign defined institution. With three such strong branches of the same religion, American, British and Canadian, a split over church government and jurisdiction was inevitable.

In 1820 the American and British Methodists divided the mission field, with the former receiving Upper Canada and the latter Lower(4). Subsequently, sometime between the years 1824 and 1828, the Canadian Conference became autonomous from the Methodist Episcopal Church of the United States(5).

Within one generation a completely Canadian form of an international body had successfully emerged. In celebration, and also to accommodate a growing congregation, Robert Petch designed a larger brick version of his 1818 church for the southeast corner of Toronto and Newgate (now Adelaide) Streets in 1832(6). The church was demolished in 1870(7).

Notes

1 Marion MacRae and Anthony Adamson, Hallowed Walls; Church Architecture of Upper Canada, (Toronto: Clarke, Irwin and Company Ltd., 1975), p.29.

2 Dendy, Lost Toronto, p.112.

3 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.210.

4 Firth, p.lv.

5 Gerald M. Craig, Upper Canada; The Formative Years 1784-1841, (Toronto: James Lorimer and Company and the National Museums of Canada, 1984), p.167.

6 Dendy, Lost Toronto, p.112.

7 Eric Arthur, Toronto, No Mean City, 3rd ed., ed. Stephen A. Otto (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986), p.113.

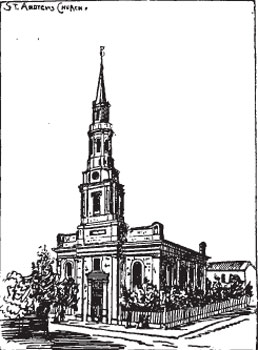

11. St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church

St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church

For both Methodists and Presbyterians, North America was yet another forum for the manifestation of Old World schisms. By 1834 there were two Presbyterian congregations in York, each taking an opposing side over the issue of state-funded religion.

The Irish Secessionist Presbyterian Reverend James Harris (1793-1873) came to York in 1820 and soon after began to organize a congregation(1). A church and lands were donated in 1821 by Jesse Ketchum [site 7, 8], Harris’ future father-in-law(2). The congregation consisted of about 400 Irish and American tradesmen and artisans(3). As part of the United Synod of Upper Canada, the Harris church did not support

The Presbyterian Church was the Church of Scotland.

Conflicts over state-funding between the two churches continued until 1834 when some of St. Andrew’s members joined with the former Harris congregation to create the Free Church(9). This new church, founded on the

Notes

1 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.36.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Armstrong, A City in the Making, p.172.

5 Ibid.

6 Firth, p.lvii.

7 Arthur, pp.46-7.

8 Ibid.

9 Martyn, The Face of Early Toronto, p.67.

10 Firth, p.lvii.

11 Ibid., p.lviii.

12. The Engine House

The Engine House

Fire. It was a reality against which the people of York fought daily to prevent.

Early legislation required a ladder on every roof, two 2-gallon water buckets hung by the front door and regular chimney sweeping(2). Fire fighting suffered in these early years because the bucket brigadiers were all volunteers, meaning not every young

On January 30,

The York Fire Company was created in 1826(7). The Hook and Ladder Fire Company was formed in 1831(8).

The Great Fires of 1849 and 1904 were a legacy of the limitations of York’s early fire prevention(10). The term “Great Fire” refers to the destruction of many buildings and over a million dollars damage(11). Such fires were extensive and burned from 1500 to 2000 degrees Fahrenheit, creating their own wind currents and atmosphere(12). Being a country rich in lake-systems, it is surprising to learn that of the estimated 528 major fires in the world from 1815 to 1915, 290 were in Canada and America(13). More directly, between 1750 and 1917, there were 61 major fires in Canada alone(14).

Notes

1 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.49.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Firth, p.lxxi.

5 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.49.

6 Ibid.

7 Firth, p.lxxi.

8 Ibid.

9 Armstrong, A City in the Making, p.171.

10 Ibid., p.251.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid., p.252.

13 Ibid., p.253.

14 Ibid.

13. The Fish Market

Town of York Fish Market

Though several sources confirm the existence of a fish market in York, they do not all agree on its location. Generally it seems that the market was near the foot of Church Street, on the beach, with wharfs nearby where ships could dock. The harbour reports of the day focused on the need for sanitary standards in the bay(1), and the lack of proper facilities such as a system of warning buoys(2).

Exactly when commercial fishing became important to York’s economy is also not known. Some information has been provided by Henry Evans, and early fisherman, who wrote in 1833 that there were already designated fishing grounds by the peninsula(3). Fishermen also learned a great deal from native practices. For example, the tradition of night fishing with torches to lure the salmon was an old native spearfishing technique(4). Anna Jameson, describing a York evening by the bay, saw “rows of red lights from the fishing boats gleaming along the surface of the water”(5).

Fishermen brought in a varied catch including salmon, white fish and bluebacked herring(6). In the winter cod and oysters were imported into the region(7). As the market was on the mainland and the fishing grounds were by the peninsula, fishermen went back and forth frequently. The lake, however, had a changing nature and often men were caught in storms far from shore. Even on a calm day valuable time could be lost in returning to shore to dry fishing nets.

As a result, in the late 1830s fishermen began establishing cabins on the Island(8). They built small temporary driftwood shanties on the poorer land(9). Between temporary homes on the island and open boats, the fishermen were often victims of the very elements which defined their livelihood.

Notes

1 Firth, p.236.

2 Armstrong, A City in the Making, p.23.

3 Firth, p.79.

4 Sally Gibson, More Than an Island; A History of Toronto Island, (Toronto: Irwin Publishing, 1984), p.6.

5 Ibid., p.44.

6 Firth, pp.327-27.

7 Ibid.

8 Gibson, p.52.

9 Ibid.

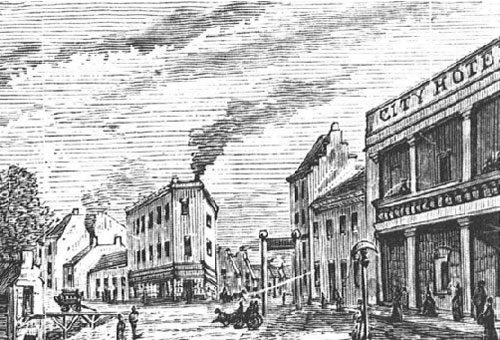

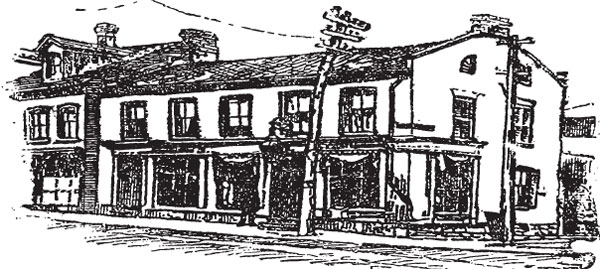

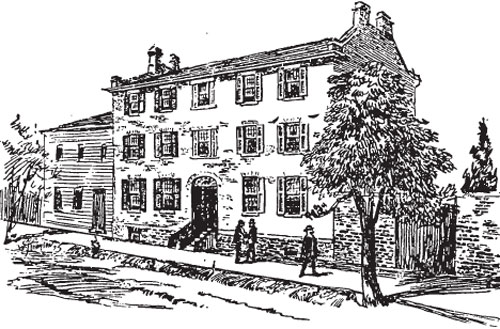

14. The City Hotel

Town of York City Hotel

With each passing year York, and later Toronto, grew demographically, commercially and residentially. Daily hundreds would brave rough sea crossings or long stagecoach journeys to join in the prosperity. As a result facilities had to exist for those people without homes of their own in the town.

The Wellington Hotel [site 3, 4] was one of the many hotels along the waterfront. Another was the Steamboat Hotel, owned by Ulick Howard(1). Located at 64 Palace Street East (now Front), Howard’s hotel was recognized for its characteristic delineation of a steam packet extending the length of the building(2).

John Bradley took over ownership of the hotel in 1829(3) . He maintained it as the Steamboat Hotel for a few years, then renamed it City Hotel, likely due the town’s incorporation into the city of Toronto in 1834(4). Bradley’s hotel was an elegant two-storey building which has been captured in several 1830s prints of the city.

The City Hotel catered largely to visitors who came by sea, and offered a wonderful view of the harbour and Gibraltar point.

Notes

1 Henry Scadding, Toronto of Old, ed. Frederick H. Armstrong, (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1987), p.19.

2 Guillet, p.75.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid

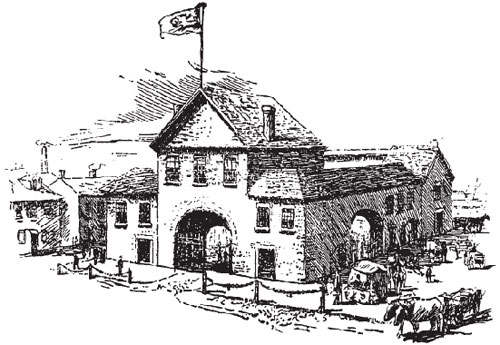

15. The Market and Town Hall

Market and Town Hall

A market was established in York in 1803(1). Despite being transferred to a long wooden shed in 1820, within a decade the market was just too small to supply the growing population(2). The town magistrates had the shed moved to a new location closer to the shoreline, and advertised for the submission of plans for a new market building(3).

James Cooper’s plan was chosen on March 22, 1831, for which he received 25 pounds sterling(4). His design was of a brick structure which stretched from Market to New (now Jarvis) Streets, between King and Palace (now Front)(5). It had arched entrances with gates on all four sides, and posts with chain railings along the front of the building(6). There were enough shops with cellars for 35 butchers, and a covered area for selling butter and eggs(7). Galleries above the shops were used to store oats or as balconies during public meetings in the courtyard(8).

This was then a dual purpose structure as it also housed York’s Town Hall. York had experienced massive waves of British and Irish immigration throughout this period. Resulting population pressure had the effect that municipal and social organization had to be put into place for the needs of York’s new middle class and urban poor, the latter afflicted by cholera epidemics atop the miseries of their impoverished state.

In response, the first bylaws in York dealt with daily short-term issues, for example the bread supply(9). Slowly a municipal level of government formed to address all new issues. They met in the Town Hall, which was housed on the second floor of the 1831 market building, above the main entrance. The quarters were described as cramped and somewhat unsafe(10).

The 1831 market and Town Hall was one of the main reasons behind York’s incorporation into Toronto. The expense of the building, which cost an estimated 9240 pounds sterling, had put the town into debt. Joining Toronto was an exercise in economic preservation. It was used as Toronto’s first City Hall until 1845, and as a market until its destruction in the Great Fire of 1849(11). Uniquely, the York Town Hall was the only one in Upper Canada during this politically volatile period(12).

Notes

1 Guillet, p.161.

2 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.72.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Armstrong, A City in the Making, p.26.

6 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.68.

7 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.72.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 William Dendy, Lost Toronto: Images of the City’s Past, 2nd ed., (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1993), p.64.

11 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.68.

12 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.74.

16. The Farmer’s Storehouse Company

16: Farmers’ Storehouse

The Farmers’ Storehouse Company was set up in 1824 by the farmers of the Home District(1). Its establishment was an economically defensive move by the farmers to protect themselves from profit-seeking merchants and middlemen.

Early York merchants were few but aggressive. They were unable to profit from the industries of York, such as breweries, tanneries or foundries, because they only produced enough for the community(2). Merchants had also been excluded from the sale of produce by the York market. However the surpluses of wheat and potash produced by farmers were ideal commodities for the merchants to export and profit from(3).

Under the existing system the merchant would assume all the risk by purchasing the farmer’s crops in advance. The merchant would store the produce and arrange their transport to Montreal, then on to Europe(4). The Bank of Upper Canada [site 33] granted the merchants annual loans to purchase the crops, which allowed them to become economically essential to the development of export trade(5).

The farmers formed a co-operative to fund their purchase of a property at the foot of New (now Jarvis) Street(6). The 100 foot long by 20 feet wide wooden building was a depot for goods going to Britain or the West Indies, and a centre for sales in York(7). Goods would be stored in the winter while the roads were passable, then transported by boat in the spring in order to obtain the best price.

The jobs of merchants and farmers were further complicated by international import laws. For instance, the British Corn Laws which prevented the importation of cheaper colonial wheat(8). The efforts made by York farmers were socially and historically important, but economically negligible in comparison to the merchants.

Notes

Robertson, I, p.218.

Firth, p.xxiii.

Ibid., p.xxii.

Ibid., p.xxiv.

Ibid.

Scadding, p.319.

Robertson, I, p.219.

Firth, p.xxv.

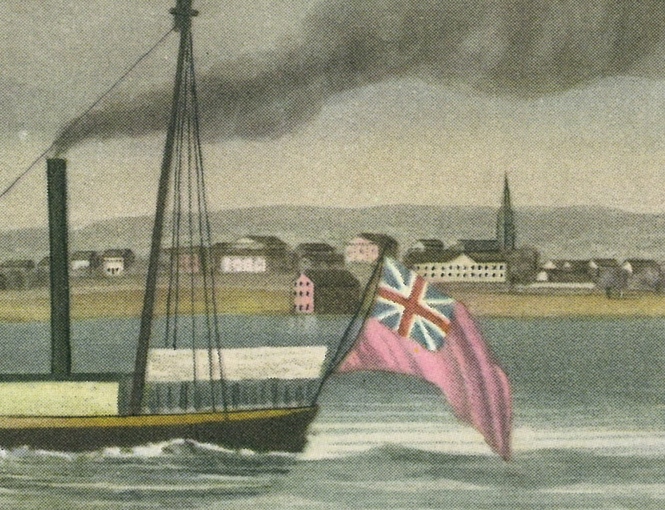

Image Credit: York from Gibraltar Point (detail), 1828. Aquatint by Joshua Gleadah, etching and watercolour on wove paper, based on a drawing by James Gray. Printed by Willett & Blanford, London.

17. St. James’ Church

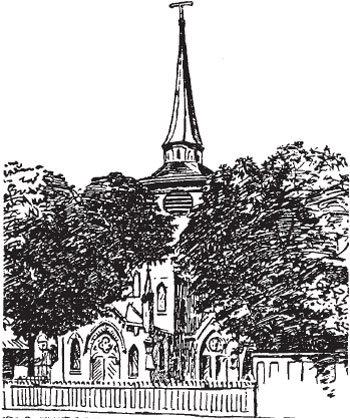

St. James Church

The Church of England was the first denomination to offer religious services in York(1). This was because many of the first settlers in Simcoe’s Upper Canada were English. They had no clergy, and held Sunday services in the Parliament Buildings(2). In recognition of this six acres of land were set aside in 1797 for the construction of an Anglican church between New (now Jarvis), King, Church and Newgate (now Adelaide)(3).

The movement to build the first St. James’ church began six years later(4). It was a small wooden building, 60 feet long by 40 feet wide, made from the pine trees which had densely covered the lot(5). The Harvard-trained George O`Kill Stuart (1776-1862) was the first rector and one of the main fundraisers behind the church’s construction(6). The first St. James’ Church in York was charming but very small. John Strachan, originally of Aberdeen, moved to York on the eve of the War of 1812(7). As the new rector, he waited impatiently for an end to the looting and dismantling of his church by American troops. Soon after the war, Strachan began to spiritually rebuild his congregation and church.

After serving thirty years as the symbol of the Church of England for the colonial outpost, the wooden St. James’ became too small to be of use to the large congregation. It burned to the ground in 1830(8). A new church of hammer-dressed Kingston limestone was designed for the same site(9). The 1831 St. James’ Church cost 12 500 pounds sterling to build and was designed in the elegant Regency style(10). The cornerstone read: James G. Chewett, architect and John Riley, builder(11). Here lies one of the many injustices of history. It was not Chewett but Thomas Rogers who was the architect of the 1831 St. James’(12). Rogers, whose training and place of origin have long since been lost, had sent his plans for a Corinthian St. James’ to Strachan in 1831(13). It would seem that not only were his original plans altered, but those involved chose to omit his name. Rogers’ limestone church lasted until the Great Fire of 1849(14).

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.501.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid., p.347.

4 Ibid., p.346.

5 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.40.

6 Ibid., p.39.

7 Ibid., p.49.

8 Martyn, The Face of Early Toronto, p.27.

9 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.206.

10 Robertson, I, p.506.

11 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.206.

12 Ibid., pp.206-08.

13 Ibid., p.207.

14 Ibid., p.208.

18. St. James’ Rectory

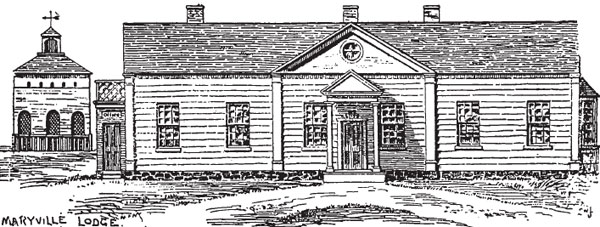

St. James Rectory

The first Anglican rector in York was George O’Kill Stuart [site 17]. Rector from 1801 to 1811, Stuart lived for a time in a two-storey stone house on the southeast corner of King and George Streets(1). In 1807 his rectory became the Home District Grammar School[site 21](2).

The second rectory was built for John Strachan, rector from 1812 to 1847(3). Strachan had been living in rented accommodations, awaiting the new rectory’s completion in 1818. Located on the north side of Palace (now Front) Street, west of York, Strachan’s home became the “Bishop’s Palace” in 1839 when he was appointed the first Anglican Bishop for the diocese of Upper Canada(4).

Depicted on our model is the third rectory in this sequence, the 1825 Newgate (now Adelaide) Street rectory, which began as a hotel(5). Andrews was the hotel’s last owner and tenant, followed by the St. James’ parish clerk, the eccentric John Fenton. Fenton was also the clerk of the Police office. Rumour was that during sermons Fenton would lie back and cover his face with a handkerchief, and remain that way until the preaching was over(6).

Henry James Grasset was the first rector to reside in the 1825 rectory. He had come to Toronto from Montreal in 1835 after being appointed as Strachan’s assistant minister(7). Grasset was made rector in 1847, and lived out his final years in the 1825 rectory.

In 1902, during the centenary celebrations of St. James’, Grasset’s rectory was demolished and replaced by a modern version, which was itself demolished in 1963(8).

Notes

1 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.47.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 John Ross Robertson, Landmarks of Toronto, Vol. II (Toronto: John Ross Robertson, 1896), p.809.

5 Ibid.

6 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.48.

7 Robertson, II, p.809.

8 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.48.

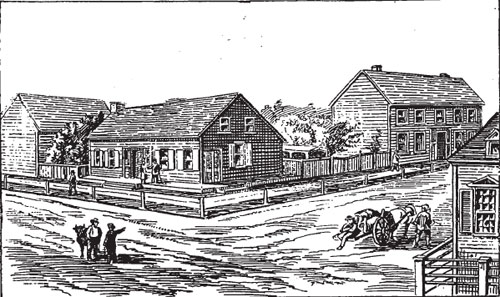

19. Irish Town

Irish Town

Canada was settled by immigrants. They have played a critical role in the defining and shaping of the country which exists today. A brief discussion of early immigration, and the ethnic and cultural questions it raised, allows for a better understanding of 1837 Toronto.

Initially over half the population of York came from the British Isles, with the largest group being the Irish(1). In 1831 over 15 471 British immigrants landed in York creating political, sanitary and cultural chaos(2).

Who were the Irish arriving at York? They were drawn from two distinct communities that were divided economically, culturally and rooted in religious conflict. The Protestants were concentrated in the northeast of Ireland, in urban centres of commerce and textile manufacturing(3). The Catholics came from the south and west, and existed mainly by subsistence agriculture(4).

As discussed in Houston and Prentice’s 1988 Schooling and Scholars in Nineteenth-Century Ontario, the Irish cultural complexity was reproduced in Upper Canada. The urban poor, who waited by the port for news of land or wage work, included both Protestant and Catholic Irish immigrants. Some settled in concentrated rural townships like the Irish Catholics of Emily Township near Peterborough. Also at this time, Catholicism in Upper Canada came almost to be defined as Irish above all else.

In the 1830s some areas of York, which had become distinctly Irish in flavour, were dubbed “Irish Towns”. There were several of these towns over the decades of the nineteenth century, with one situated south of Newgate (now Adelaide) and east of the church plot(5). The Irish Towns were a cultural manifestation of ethnic and economic solidarity in early Upper Canada.

Notes

1 Susan E. Houston and Alison Prentice, Schooling and Scholars in Nineteenth-Century Ontario, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988), p.280.

2 Firth, p.lxxxii.

3 Houston and Prentice, p.280.

4 Ibid.

5 Scadding, p.109.

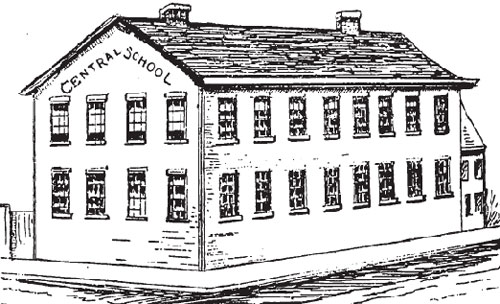

20. Upper Canada Central School

Upper Canada Central School

Under the Common School Act of 1816, a school was built by public subscription on the northwest corner of Newgate (now Adelaide) and New (now Jarvis)(1). Thomas Appleton of Yorkshire was the first schoolmaster(2). However Appleton left his post the following year when his Common School became Upper Canada Central School(3).

As his first act in office, Lieutenant-Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland wanted the newly created Central School to be run as a government-funded Andrew Bell Monitorial School, similar to the National Schools of Britain(4). Bell Schools were based on and taught the tenets of the Church of England(5). His first instructor, Joseph Spragg(e) (1775-1848), incorporated the Bell method with the Lancastrian, which was to have older children teach the younger(6).

The principle was economical, many students to few teachers, and put forth the views of the Church. Maitland was criticized for his tactics by many people, including Jesse Ketchum [site 7, 8](7). His critics felt he was sacrificing non-denominational education by replacing it with a church school. The Anglican orientation was too obvious, and Spragg(e) was criticized for his methods.

During the Upper Canada Central School’s 24 years in operation 5 514 pupils, male and female, were taught free of charge in the government sponsored school(8). However the school never recovered from the prejudices against it. Both Spragg(e) and the school retired in 1844, making funding available for those private non-denominational schools which had sprung up as a result(9).

Notes

1 Firth, p.145.

2 Ibid., p.143.

3 Ibid., p.145.

4 Francess G. Halpenny, gen.ed. Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. VII (Toronto and Quebec: University of Toronto Press and Les Presses de l’université de Laval, 1988), p.822.

5 Ibid.

6 Firth, p.143.

7 Halpenny, VII, p.822.

8 Firth, p.xlvii.

9 Halpenny, VII, p.822.

21. Home District Grammar School

Home District Grammar School

Secondary schools were called grammar schools until 1871(1). The York District Grammar School began in 1807 under Reverend George O’Kill Stuart [site 17,18](2). Stuart taught 5 boys, for a fee, in the rectory. His calling however proved to be more as rector than as headmaster.

Unlike his predecessor, John Strachan [site 17,18] was a born teacher. He began when he was 16 in his hometown of Carmyllie, Scotland(3). Strachan initially came to Canada in 1799 for a tutorship in Kingston, and as a result became an active supporter of the 1807 Act to establish a grammar school in each district of the province(4). When Strachan received his posting as rector in York, it was inevitable that the new grammar school would occupy some of his time.

In 1816 the Court of the Quarter Sessions [site 5] agreed to grant 400 pounds sterling to build a schoolhouse on the southwest corner of College Square(5). This six acre lot was bounded by Newgate (now Adelaide), Hospital (now Richmond), New (now Jarvis) and Church(6). The building had two storeys, the main floor for classes and the upstairs for public debates and lectures, which subsidized the painting of the school blue(7). Strachan taught 50 boys per year, all from leading families. The subjects were English, elocution, arithmetic, bookkeeping, mathematics, civil history, natural history (science), geography, Latin, Greek and religion(8).

Strachan had many critics. They saw his school as elitist, and too rooted in the Church of England(9). Admittedly, Strachan saw himself to be in the business of creating future leaders, and so he demanded a high level of education and instructed only those for whom leadership was possible. In 1825 the “Blue School” became the Royal Grammar School(10). Then in 1830 it combined with Lieutenant-Governor Colborne’s Upper Canada College(11).

Together they moved to the present site of Upper Canada College, then separated in 1834 over curriculum(12). The Grammar School (formerly the Blue School) returned to its original location, and remained there until 1864 when it moved to Dalhousie Street and admitted female students.

Notes

1 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.57.

2 Ibid.

3 Robertson, I, p.115.

4 Ibid., p.116.

5 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.57.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Firth, p.xlvii.

9 Ibid., pp.xlvi-xlvii.

10 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.58.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

22. Baptist Chapel

Baptist Chapel

The origins of the Baptist Church in York have not yet been discovered. Two of the stronger theories are that either American Baptist missionaries introduced it, or it was the Loyalist Baptists from New England who settled in Nova Scotia, Quebec, the Niagara Peninsula, the Bay of Quinte and the shores of Lake Erie in 1812(1). In either case the root can reasonably be said to be American, which seems probable as for a time the Baptist Churches of Upper Canada were funded by the American Baptist Home Missionary Sociey(2).

Baptist theology is based on the saving ordinance of adult baptism. Total immersion in water as a sacrament of spiritual rebirth to full church status serves as a communicant of their faith. However this had certain architectural implications, and often in early churches it was impossible to have such special function areas built(3). More often than not necessity reduced choice, which is why so many early churches and chapels of whatever denomination were square and made of wood(4). As a compromise Baptist Chapels in particular tended to be located near to a large body of water(5).

A small Baptist congregation was organized in York in 1829, and three years later a chapel was built on March Street(6). The 1832 chapel was made of brick, and built to a square plan(7). The Reverend was Alexander Stewart, a clergyman and author from the Highlands of Scotland(8). He had served as a missionary in his own country before coming to Canada in 1818 to be a teacher(9). However Stewart tendered his resignation in 1836 because of dissension within the congregation(10). The chapel was closed and rented to other denominations, including the Negro Baptists(11).

Generally York’s early Baptist congregation was small in number and impact(12). Yet by its continued existence it has furthered the religious history of Toronto.

Notes

1 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.66.

2 Craig, p.168.

3 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.67.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Firth, p.lx.

7 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.241.

8 Ibid.

9 Firth, p.lx.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

23. Joseph Cawthra’s House

Joseph Cawthra’s House

The one and a half storey frame house that stood on the northwest corner of Frederick and Palace (now Front) was home to a succession of three of the most dynamic personalities in the history of Toronto.

First it was the home of William Warren Baldwin and his new bride Margaret Phoebe Willcocks. The Baldwins were married in 1803, and moved a year later into the home built for them by Margaret’s father, William Willcocks(1). It was then the Baldwin family home as well as a school, run by Baldwin, for a time. The Baldwins moved in 1807 and Willcocks rented out the house until his death in 1813, when his daughter Maria sold it for 500 pounds sterling(2).

The next interesting occupant of Baldwin’s former home was William Lyon Mackenzie (1795-1861). The Mackenzies, all ten of them including in-laws and apprentices, took up residence in 1824(3). The family lived at the rear of the house, while the front was the printing office for Mackenzie’s The Colonial Advocate. Due in part to his outspokenness against the Tories, his shop was raided in 1826 and the press was destroyed(4). Mackenzie was on the verge of bankruptcy, but the profit he made in court over damages from the raid restored him financially. They moved that same year.

In 1837 the house was owned by Joseph Cawthra (1759-1842). Natives of Gesley, Yorkshire, the Cawthras moved to York in 1806(5). Cawthra opened an Apothecary from which he made a fortune by supplying the British army during the War of 1812(6). He then expanded his store at King and Caroline into a retail and wholesale grocery store, specializing in tea and tobacco.

Joseph Cawthra lived in the house at Frederick and Palace until his death in 1842(7). The house was later destroyed by fire leaving behind a vacant lot and some impressive ghosts.

Notes

1 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.30.

2 Ibid., p.31.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Dendy, 2nd ed., p.112.

6 Ibid.

7 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.31.

24. Russell Abbey

Russell Abbey

Elizabeth Russell (1754-1822) was unlike most women of her class. She was older, had less education and never married(1). Having cared for her violently insane mother up until the age of 25, Elizabeth came from a world of extravagance, illness, lawsuits and debt. After the death of her mother in 1770, and father in 1786, she was taken under the wing of a half-brother she hardly knew(2).

Peter Russell (1733-1808), who was 20 years older than Elizabeth, first met his sister in Ipswich when he was 38. His career in Upper Canada lead to an appointment in 1792 as Receiver-General of Ontario(3). Elizabeth went with him, and settled in Niagara-on-the-Lake. Peter placed his illegitimate daughter Mary Fleming under his sister’s care, but unfortunately Mary died soon after of tuberculosis(4).

In shock from the loss, Elizabeth went to join Peter in York. Peter was having Russel Abbey, a home named after the Russel family seat at Wolburn Abbey, built for him and his sister on the northwest corner of Palace (now Front) and Prince’s Streets(5). With construction complete upon her arrival, Elizabeth moved into the beautiful estate which overlooked the lake. There for many years, while Peter administered the province, Elizabeth longed for England. Together they entertained York society, and nursed Peter’s failing health.

Peter had been trying to sell his property so that they could return to England, but died in 1808 without an offer(6). William Warren Baldwin [site 23], the Russels’ closest friend, helped Elizabeth settle her brother’s estate. She was his sole heir, and never recovered from the loss. Possibly it was her grief and depression which deteriorated into mental illness, such that by 1812 the Baldwins had moved into Russel Abbey to care for her.

Elizabeth died in 1822, willing the Russel Estate to her cousins Margaret Phoebe Baldwin and Maria Willcocks(7). As a legacy, the letters and diary of Elizabeth Russel paint a detailed picture of the life of a unique woman in early Upper Canada.

Notes

1 Francess G. Halpenny, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. VI, (Toronto and Quebec: Universoty of Toronto and Les Presses de l’universite de Laval, 1987), pp.669-70.

2 Ibid.

3 Eric Housome, Toronto in 1810; The Town and Buildings, (Toronto: Coles Publishing Company Ltd., 1975), p.64.

4 Halpenny, VI, p.670.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid., p.729-32.

7 Ibid., p.670.

Image Source: Toronto Public Library

25. The Crown Inn

The Crown Inn

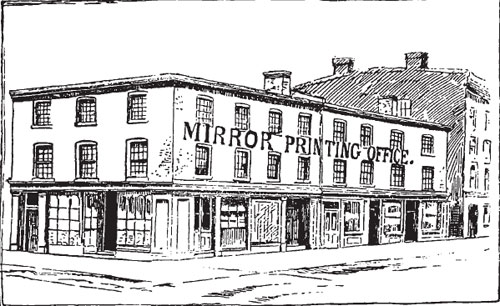

With a few bricks Joshua Beard turned a cabbage patch into a hotel, a tailor’s shop, a printing office and a grocery store. Beard was helped by the 1826 economy which was alive with entrepreneurs. His clever selection of a central property lot, on the southeast corner of King and New (now Jarvis) Streets, was also paramount to his success(1). Though initially he built the small frame building to be a store, it soon took on a less modest role.

Thomas Moore was the first to see promise in the site. By 1830 he had opened a hotel on the site called the Crown Inn, with a crown as its symbol(2). Moore also relocated his tailoring business to it, which had been on the northeast corner of King and Princess Streets(3). The Inn had no stables, and was probably patronized by local tradesmen.

The Crown Inn was open for business for about 10 years(4). In that time several other businesses had space in the building. The printing office of George Gurnett’s (1792?-1861) Courier of Upper Canada was upstairs of the Inn from 1829 until 1837(5). Gurnett had been in the newspaper business for many years, and retired only when elected Mayor in 1837. In all he served four terms as Mayor of Toronto(6).

After Moore closed the Crown Inn, William Henderson’s Grocery Store occupied the main floor of the building(7). Dunlevy, in the footsteps of George Gurnett, printed his newspaper, the Mirror, above Henderson’s store(8). A decade earlier the Mirror sign in the picture likely read Courier, with a second sign beneath it of a crown.

Notes

1 Firth, p.87.

2 Robertson, I, p.393.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 W. Stewart Wallace ed., The MacMillan Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 3rd ed. (Toronto: The MacMillan Company of Canada Ltd.,1963), p.287.

6 Ibid.

7 Robertson, I, p.393.

8 Ibid.

26. William Proudfoot’s Wines and Spirits

William Proudfoot’s Wines and Spirits

A clever merchant with his wits about him could quickly become a wealthy man in York. William Proudfoot, who arrived in Upper Canada from Scotland after the War of 1812, aimed to do just that(1).

D’Arcy Boulton Jr. owned and operated a store on the southwest corner of King and Frederick(2). With an establishment already in place, Proudfoot got himself employed there and worked his way up to partner. The partnership dissolved in 1825, with Proudfoot becoming sole proprietor(3).

The building was a large frame structure, made of white painted brick(4). It was valuable real estate because of its size and central location in the mercantile district. Proudfoot prospered by selling desirable merchandise such as ostrich feathers, Italian lute strings, black crepe, copper tea kettles, silk and cotton umbrellas and beaver caps for children(5).

Proudfoot devoted ten years to building up a prosperous business, but decided to retire in 1835 to pursue public life(6). In that same year he became the president of the Bank of Upper Canada and held that position until 1861, living at the glamorous Kearnsey House for most of those years(7).

Notes

1 Firth, p.66.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Robertson, I, p.25.

5 Ibid.

27. First Bank of Upper Canada

First Bank of Upper Canada

William Allan was one of the wealthiest men in Upper Canada. His affluence was expressed not only in money, but in property, architecture and status. He owned Moss Park [site 50], which was his country estate; the former Frederick Street Post Office and Custom House; and a solid brick building on the southeast corner of Frederick and King(1).

The building had changed somewhat over the years but originally it had an arched central entrance, with lined-up windows on the first and second floors(2). It was here that Allan owned and operated a general store from 1818 until 1822(3).

Allan had been a strong supporter of York’s petition to be granted a charter to open a bank. This was granted in 1819, and with that the leading citizens of York began the search for an appropriate location for the new bank(4). It was decided that Allan’s store would provide the site as it was very central and Allan was a willing landlord.

The first Bank of Upper Canada opened in 1822 on the southeast corner of King and Frederick(5). William Allan was the President, and the incorporators were Robert C. Horner, John Scarlett, Francis Jackson, William W. Baldwin [site 23], Alexander Legge, Thomas Ridout [site 37], Samuel Ridout, D’Arcy Boulton Jr. [site 26], William B. Robinson, James Macaulay, Duncan Cameron, Guy C. Wood, Robert Anderson and John S. Baldwin[site 28](6).

The bank itself was in the corner section of the building, marked by the large window, with its entrance on Frederick Street(7). The vault had an iron door, and was placed in the western part of the cellar(8). The bank remained at this location until it outgrew the space. After purchasing land on the northeast corner of Duke (now Adelaide) and George Streets from Judge William Campbell [site 36] in 1827, the Bank of Upper Canada moved to its second location(9).

The first Bank of Upper Canada became William Gamble’s Wholesale establishment, notably the first one of many in York(10). It subsequently became a brewery, a boot store and a fruit store, until it was demolished in 1915(11).

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.15.

2 Ibid.

3 Martyn, The Face of Early Toronto, p.18.

4 Robertson, I, p.15.

5 Martyn, The Face of Early Toronto, p.18.

6 Robertson, I, p.15.

7 Ibid., p.16.

8 Ibid.

9 Martyn, The Face of Early Toronto, p.18.

10 Robertson, I, p.16.

11 Martyn, The Face of Early Toronto, p.18.

28. St. George House

Quetton St. George (later Baldwin) House

Another interesting figure in the history of York was Laurent Quetton St. George. Even the man’s very name is shrouded in mystery.

Laurent and his brother Etienne were young Royalists who left France in 1791 to enlist in a guerrilla force of French emigres that was forming in London(1). They adopted the name St. George in order to protect their family. When both brothers returned to the Revolution, Etienne was killed, forcing Laurent to once again flee to England. However another story claims that Laurent alone changed his name because he wanted to commemorate that his first step on English soil was on St. George’s Day(2).

St. George came to Upper Canada in 1802 and quickly made a career in the fur trade(3). In 1807 he came to York, started a business, and with his profits built a beautiful Georgian home on the northeast corner of King and Frederick Streets(4). The building was residential, except for the main floor which served as a store with cellars below for storage. The brick from which it was built likely came from the excavated material of the lot(5). Brick was a rarity in York, making St. George’s house a definite symbol of prosperity and affluence.

St. George took his pre-1812 fortune and returned to France for the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1815(6). John Spead Baldwin, brother of William Warren Baldwin, bought St. George’s house and lived in it, later renting half of it to the Canada Land Company [site 30].

Notes

1 Dendy, 2nd ed., p.90.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., p.91.

6 Ibid.

29. Daniel Brooke Building

Daniel Brooke Building

Daniel Brooke (1792?-1872) was a merchant in nineteenth century York(1). He and his brother-in-law Henry Dean were partners in a shop(2). Brooke also had a store in Niagara, and later became a lawyer in Brantford.

While in York Brooke was enterprising with his time and finances. He studied the economic environment in relation to important locations in the town. The northeast corner of New (now Jarvis) and King Streets was very central which is what prompted Brooke to build a hotel there. The structure he built in 1833 was a hotel and livery stable mainly for the use of farmers when they came to market.

Since that time the site has known a series of occupants. Wholesale grocer James Austin, who later founded the Consumer’s Gas Company and the Dominion Bank, had offices there. The building was also the printing office for The Patriot, a conservative newspaper.

Brooke’s large business block is a rare example of Georgian architecture in the commercial centre of town. The building was rebuilt in 1848, and survived the Great Fire of 1849 quite well. In recent times an extensive restoration program was carried out on Brooke’s building, returning it to its former glory. Excluding the price of the real estate, the Brooke-Murchison Block Company restoration project cost roughly three million dollars.

Notes

1 Firth, p.44.

2 Ibid.

30. The Canada Company

The Canada Company

The Canada Land Company was in 1837 on the east side of Frederick Street between King and Palace (now Front), in a building designed by John G. Howard. Perhaps more interesting than its architecture was the company’s evolution.

The War of 1812 had many immediate as well as long-term consequences. Particularly for those people in York who had their homes and lives upset, the process of rebuilding was long and expensive. However, as York was a colonial settlement, the home government of Britain had certain obligations.

It was these obligations that John Galt was employed to pressure the government for on behalf of the colonists(1). The residents’ claims for losses and damages from the War had been ignored by Britain, such that by 1815 there was growing discontent(2). For a fee, Galt served as their spokesman, and managed to get the British government to pay a portion of the debt in 1820(3).

However this was all they would pay unless the provincial government of Upper Canada would match their payments or take over some of the funding of the province(4). Galt determined that, since the colonial government had no capital, Crown and Clergy Land Reserves should be used to create revenue. This was to be done by establishing a land company, with Galt, the outspoken Scottish novelist, as its Superintendent(5).

Land companies had been used in America and Australia to develop unpopulated regions(6). Its role was to attract settlers by preparing the land, providing employment for immigrants, making loans to settlers, promoting Canadian land overseas and improving on communication and agriculture in the province(7).

At the request of Bishop Strachan, the Clergy Reserves were removed from the agreement(8). Therefore at the time of the company’s founding in August 1826, they owned 1 100 000 acres (including the Huron Tract), for which they paid sixteen annual payments of approximately 15 000 pounds sterling to the Receiver General of Upper Canada(9).

Despite Stachan words of advice, Galt did not manage to endear himself to the Family Compact. The company directors in London lost faith in him, and Lieutenant-Governor Maitland saw him as unsound(10). He was later replaced by Thomas Mercer-Jones, future son-in-law of John Strachan(11).

Opinion seems to be divided as to whether the Canada Land Company was beneficial to Upper Canada. From 1826 until 1950 it brought new life to land settlement, and created large amounts of capital from which one third could be used for public works(12). However its establishment coincided with the immigration of the 1830s which brought people regardless of their overpriced land lots. Also Reformers were suspicious of the English stockholders who controlled the company from across the ocean(13).

Notes

1 Craig, p.134.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid., p.135.

5 Ibid., p.137.

6 Ibid.

7 Clarence Karr, The Canada Land Company, The Early Years, (Ottawa: Ontario Historical Society Research Publications #3, 1974), p.9.

8 Craig, p.136.

9 Ibid., p.135.

10 Ibid., p.137.

11 Ibid., p.138.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

Image Credit:

City of Toronto – Toronto Culture, Museums and Heritage Services, Reference No. 1978.41.60

31. York’s Third Post Office

York’s Third Post Office

York’s third Post Office, a two-storey frame building on the west side of George Street below Duke (now Adelaide), opened in 1830 under Postmaster James Scott Howard(1). As Postmaster, Howard was responsible for providing and equipping a Post Office building, and paying for staff(2). It was a large outlay, however, the Postmaster claimed some of the postal profits of the sales which made it one of the most lucrative positions in York(3). This was a unique Post Office as it was the first to offer patrons individual post office boxes(4).

Howard (1798-1866) was a native of County Cork in Ireland. His unique ancestry began with his grandfather Nicola Huart (or Houard), a Huguenot who fled France when the Edicts of Nantes were revoked, ending toleration of Protestants(5). Nicola first went to Holland, then reunited with his family in England to finally settle in Ireland(6). Once in Ireland, Huart became Howard.

The young Irishman first landed in Fredericton, New Brunswick, then moved to York in 1820(7). He worked in the Post Office under William Allan [site 27, 50] until being appointed Postmaster in July 1828(8). Howard’s appointment was met with some local opposition because he was a Methodist at a time when York had a predominantly Anglican population(9). Prejudices were expressed by their reluctance to let Howard handle their mail, and likely were a factor in Haward’s ultimate dismisal.

Howard was the third Postmaster in York, following William Willcocks and William Allan respectively. He proved successful and enterprising, and held the office of Postmaster for a total of eighteen years. Postal operations in York’s third Post Office continued until the opening of the Duke Street Post Office [site 34].

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.57.

2 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.70.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Sheldon and Judy Godfrey, Stones, Bricks and History, 4th ed. (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1984), p.25.

6 Ibid.

7 Firth, p.193.

8 Ibid.

9 Godfrey and Godfrey, p.26.

32. Simon Washburn’s House

Simon Washburn’s House

Simon Ebeneezer Washburn (1793?-1837) was warmly regarded by the people of York for his devotion to ice skating, despite his portly figure, and for his eccentricity in wearing York’s first monocle(1).

Washburn was born into a prominent loyalist family in Upper Canada(2). He studied law under William W. Baldwin [site 23], passed the bar in 1820 and shortly after went into partnership with Baldwin. In 1825 he established his own practice(3). Three years later, he was appointed the Clerk of the Peace for the Home District, a position he held until his death in 1837.

As Clerk, Washburn administered the Court of the Quarter Sessions, kept court records and performed oaths(4). With his new prosperity Washburn bought a home on the northwest corner of George and Duke (now Adelaide) Street. The brick structure was his only home in York.

Washburn also entered politics, but was unsuccessful and lost twice to the powerful Reformer William Lyon Mackenzie. However he made Alderman of St. Davis’s Ward in 1837, the same year he married the lovely Margaret Fitzgibbon(5).

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.454.

2 Halpenny, VI, p.896.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

33. Bank of Upper Canada

Bank of Upper Canada

In 1815 there were no banks in Canada(1). An economy of promissory notes, permeated slightly by British paper money during the war, lead to two early petitions to the House of Assembly for banking institutions(2). Kingston petitioned in 1817, and a year later York did the same under the leadership of Rev. John Strachan [site 17, 18, 21](3). After some deliberation the 1821 charter was granted to York.

The Bank of Upper Canada was an early government-allied monopoly. One quarter of its stock, over 2000 shares, was subscribed by the Family Compact dominated government(4). They, in turn, selected all fifteen directors of the bank and used their power of granting or refusing loans to gain support(5). William Allan [site 50, 27], one of the wealthiest men in the province, was the bank’s first president, followed by William Proudfoot [site 26] in 1835.

While other towns requested banks, legislation was passed to protect the dominance of the Bank of Upper Canada. For example, the powerful Bank of Montreal was pushed out of York by the 1824 Act which restricted banks to collecting accounts in the currency of their respective province(6). Though only enforced for three years, this restriction was sufficient to ensure the early success of the Bank of Upper Canada.

Credited with being the first chartered bank in Canada, the Bank of Upper Canada was not only the economic stimulus behind the commercial success of York, but is today the oldest existing bank building in the country(7). Its stately architecture seems to reflect the stature of these claims. The 1827 bank was on the northeast corner of Duke (now Adelaide) and George Streets, and was designed by civil engineer Francis Hall(8). It was the second building occupied by the bank, the previous one being established on the southeast corner of King and Frederick Streets [site 27].

Hall’s original plans for the 1827 Bank were simplified following his resignation before the building was complete. Inspired by the late 18th-century West London Georgian townhouses, Hall’s Queenston stone three-storey bank had two upper floors which served as living accommodations for Thomas Gibbs Ridout (1792-1861), the first General Manager(9). The grounds consisted of a cow shed, stables and a carriage house. The bank formed part of what now seems to be a row of buildings, but were initially four distinct structures.

Unique for 10 years, and dominant for 40, the Bank of Upper Canada was one of the many building blocks of the country. It failed in 1866(10).

Notes

1 Firth, p.xxviii.

2 Ibid., pp.xxviii, 45.

3 Ibid., p.xxviii.

4 Craig, p.162.

5 Ibid.

6 Firth, p.xxviii.

7 Margaret McKelvey and Merilyn McKelvey, Toronto Carved in Stone, (Toronto: Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1984), p.12.

8 Arthur, p.75.

9 Dendy, 2nd ed., p.235.

10 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.56.

34. Toronto’s First Post Office

Toronto’s First Post Office

James Scott Howard was Postmaster of York during a time of conflict and change. A rapid increase in population, an uprising in radical political fervour and the incorporation of Toronto all contributed to the sentiment of change and chaos(1). Population growth was the main factor that caused Howard to build this larger Post Office. It became the fourth Post Office in York, and the first one of Toronto.

Howard bought the land for 500 pounds sterling from the Bank of Upper Canada, after negotiating with President and former Postmaster Wiiliam Allan [site 50, 27](2). It was the eastermost sixty feet of the Bank’s lot on Duke (now Adelaide) Street. The agreement of sale specified that the new Post Office would be a respectable brick building to match its stately neighbour. This was not difficult for Howard, who was the highest paid Postmaster in Upper Canada(3).

A staff of six kept Howard’s Post Office in operation. It was the busiest Post Office in Upper Canada, serving a population of over 9 000(4). Postage was written by hand directly onto the letters prior to the development of the modern stamp, and red ink was used to cancel the payment notation. Hours were from 8am to 7pm Monday to Saturday, and 9am to 10am on Sunday. People were notified in the newspaper that mail had been received for them, as a daily trip to the Post Office was not always possible or necessary.

The Rebellion of 1837 caused disturbances across York. It was an embarrassment for the colony’s Postal Service as many Postmasters were found to be open sympathizers of the Reform movement(5). Post Office Surveyor, Charles Albert Berczy (1794-1858), was employed to examine all York mail for signs of treachery. Howard had always been a neutral figure, friendly to both sides, not even daring to vote and for this reason people had long been suspicious of him.

Berczy discovered that a letter sent to Howard was found to have a second letter inside it to be forwarded to a Reformer in York. For this Howard was considered a traitor and was dismissed. Berczy was made the next Postmaster, and in 1839 the Post Office moved to a new location.

Later during the block’s restoration by Sheldon and Judy Godfrey, Judy discovered that the building had originally been built as a Post Office. Her research indicates that the Duke Street Post Office is the oldest remaining building in Canada built as a Post Office(6).

Notes

1 Godfrey and Godfrey, p.25.

2 Dendy, 2nd ed., p.235.

3 Godfrey and Godfrey, p.28.

4 Ibid., p.26.

5 William Smith, The History of the Post Office in British North America 1630-1870, ([New York], 1921; rpt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973), p.213.

6 McKelvey and McKelvey, p.12.

35. John Sleigh’s House

John Sleigh’s House

The butchers, the bakers and the candlestick-makers all lived and worked in York, after all a town could not survive on politics alone. John Sleigh, a York butcher, ran his business in the market district for many years before moving to Yorkville. However unlike his fellow merchants, his home was not above his shop.

Sleigh was a tenant of lady Baldwin who owned a rental property in a very prestigious quarter of town. Built in 1835, Sleigh’s house was a two-storey rough-cast house, located on the north side of Duke (now Adelaide) Street. It is not known exactly how long Sleigh occupied the home, or how lady Baldwin came into possession of it(1).

A list of Sleigh’s neighbours reads like a “Who’s Who” of 1837 Toronto. East was the Campbell Mansion [site 36], home of Chief Justice Sir William Campbell. His son, also William Campbell, became the Clerk of the Assize in York and for a time lived in the Sleigh home. West, adjoining the structure, was James Scott Howard’s Post Office and residence [site 34], and beyond that the Bank of Upper Canada [site 33]. Opposite Sleigh’s house was William Proudfoot’s home [site 34] until he moved to Kearnsey House(2).

Though little information exists concerning either John Sleigh or his business efforts, his home is noteworthy as that of a commercially successful merchant in 1837 Toronto.

Notes:

1 Robertson, I, p.180.

2 Ibid.

36. Campbell House

Campbell House

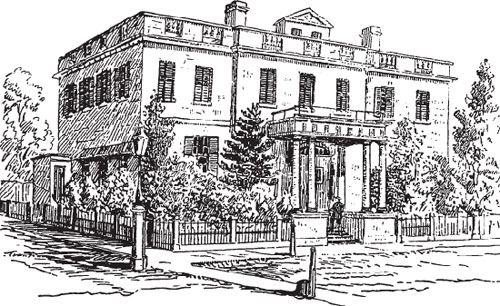

William Campbell was born in 1758 in Caithness, Scotland. These Campbells were a branch of the Diarmid clan who had emigrated north to Caithness in the late 17th-century(1). William was well educated and lived comfortably until he heard news of the rebellion in the American colonies. Against the advice of many, he joined the 76th Foot, a Highland Regiment(2).

Despite his efforts Campbell was captured in Yorktown, Virginia in 1781(3). He arrived a refugee at Chedabucto Bay, Nova Scotia in 1784. Thanks to his education and enterprising nature, Campbell became a lawyer. His appointment as Attorney-General for Cape Breton Island lead to his 1811 appointment to the King’s Bench in Upper Canada(4). In 1825 he was appointed Chief Justice of Upper Canada, and was knighted upon his retirement in 1829(5).

Sir William Campbell’s prestigious career was mirrored in the magnificence of his home. The late neoclassical style brick house was built on Duke Street (now Adelaide) at the head of Frederick Street. It was on a slight elevation which offered a view of the town and harbour. Some unique architectural features of the house included an oval window in the pediment, elegant tall windows along the front, and a curved staircase(6).

The Campbell home changed hands many times following the death of Sir William in 1834. It was the home of James Gordon, John Strathay and later a vinegar warehouse. The final commercial owner was Coutts Hallmark Co., which bought the house in 1962 and targeted it for demolition(7). However they instead decided to donate it to the Advocates Society, a group of heritage conscious courtroom lawyers, who arranged for the home to be moved to land donated by the Canada Life Insurance Company (8).

On Good Friday, April 1, 1972 the 300-ton, 41 foot high, Campbell home was moved to the northwest corner of Queen Street West and University Avenue. A grant from the Ontario Heritage Foundation allowed the Advocates to restore the home(9). Campbell House was reopened in 1974 by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother.

Notes

1 Halpenny, VI, p.113.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Robertson, I, p.80.

5 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.38.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid., p.39.

37. The Ridout Home

The Ridout Home

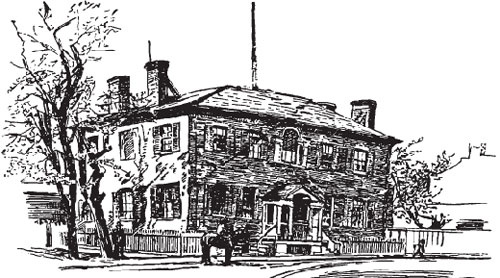

In 1822 Surveyor-General Thomas Ridout Sr. (1784-1829) and his wife Mary owned a stately single-storey house on the north side of Duke Street (now Adelaide), east of the head of Prince’s Street(1). Its setting on the wooded lot gave the Ridout home a certain prominence, as did the portico entrance. Behind the house was the family graveyard, used only briefly until public cemeteries were established.

The Ridouts were for many generations prominent citizens in the life of York. Thomas Ridout Sr. was a native of Sherbourne, Dorset in England. He emigrated to Maryland in 1774 and despite the growing rebellion, Ridout was seen as a colony-supporter(2). On a journey to Kentucky, with orders from George Washington to explore and settle there, Ridout was captured by Shawnee Indians(3). He was held for 3 months then released in British-held Detroit. Soon after he found himself in Montreal which eventually lead him to York.

Because of his support, conservative views and success as Surveyor-General (1810-1829), Ridout became part of the growing Family Compact(4). Other powerful families included their neighbours, the Jarvis family. The two families clashed frequently, culminating in a duel in 1827 between Thomas’s son John and Samuel Peters Jarvis Jr. [site 49](5). John died and Samuel was charged, jailed and acquitted. The jury found him not guilty because duelling was seen as the appropriate recourse for a gentleman to defend his honour.

Mary Ridout owned the property for 10 years. It eventually fell into disrepair and was demolished. The Ridout house was a good example of an early Canadian family home. In its day it was solid and durable, able to withstand the varying degrees of winter cold and summer heat.

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.281.

2 Halpenny, VI, p.647.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Chris Raible, Muddy York Mud; Scandal and Scurrility in Upper Canada, (Creemore: Curiosity House, 1992), pp.69-76.

38. The Arnold House

The Arnold House

Whether commercial or residential, Georgian architecture was prominent in York. Blacksmith Isaac Perry’s 1829 Georgian double house on the east side of George Street, north of Duke (now Adelaide) was an example of Georgian style comparable to Howard’s Post Office [site 34](1). Perry’s residence was equally fashionable with spacious rooms and three-storeys. Its difference lay in the purpose of the structure.

In 1834 Perry’s house came under the ownership of Hamilton resident John Arnold. It is not clear whether Arnold rebuilt or preserved Perry’s original house. However Arnold chose to become an absentee landlord, and rented-out the double house. City of Toronto Assessment Rolls of the day cite Arnold as the owner, William as landlord and a series of various tenants.

The Arnold house contrasts with the stately Campbell house [site 36] as it was not a family home but a rental property. They were large buildings, and Arnold likely had some difficulty finding tenants because most renters preferred areas slightly west or to the north, not so close to the city centre. Two known tenants were Mrs. Crombie’s school from 1852-60 on the left, and on the right, Robert Manners, a relative of the Duke of Rutland(2).

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.34.

2 Arthur, p.57.

39. The British Wesleyan Methodist Chapel

The British Wesleyan Methodist Chapel

Wesleyan Methodism began in the classrooms of Oxford University where students, under John Wesley, attempted to order their lives to include both academics and good work(1). They were dubbed “Methodists” by skeptical observers.

Wesley explored his Methodism in preaching halls, while maintaining a connection with the Church of England. So although students would meet in the halls, they would continue to receive the rites of Holy Communion, marriage and baptism, and be ordained as clergy through the Church of England(2). In 1791 the Wesleyan Methodist Church severed all ties with the Church of England and became an autonomous body(3).

Under an agreement with American Methodists in 1820, British Wesleyan Methodists were allocated Lower Canada as a missionary area(4). However, following a later split between the American and Canadian Methodist Conferences, and the subsequent departure of the Americans, the British returned to Upper Canada.

The presence of British Wesleyan Methodists in York was noted in two places. First in 1819 where they were part of the American-based Methodist Church congregation, but chose to leave it and worship at a small chapel on George Street. Then upon their return to Upper Canada in 1832 under Reverend Donald Fraser, the British Wesleyan Methodists built a wooden chapel at the same site on George Street(5).

The two chains of Methodism existed in a union from 1833 until 1840 when there was a return of the earlier dissension(6). The divisions within the churches were not over doctrine but administration and politics.

Notes

1 MacRae and Adamson, Hallowed Walls, p.29.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Firth, p.lv.

5 Robertson, I, pp.556, lvi.

6 Firth, p.183

40. Presbyterian Burial Ground

Presbyterian Burial Ground

As a British colony, the British government made a variety of arrangements on behalf of its citizens in Upper Canada. Early in the settlement of York, the British government made a series of three land grants for English, Irish and Scottish burial grounds(1). The English cemetery was on the site of St. James’ Cathedral. The Irish burial grounds were on the corner of Lot (now Queen) and Power, site of St. Paul’s Church. Finally, the Scottish or Presbyterian burial grounds were situated on the north side of Duchess Street (now Richmond), near Sherbourne(2).

When Potter’s Field, and later the Necropolis, were established many of those buried at smaller graveyards were re-interred there. The Presbyterian burial ground was elevated and returned to a pasture lot. A carpenter was the first to own the newly available land, on which he built a large frame structure. It was later demolished. Next cottages were built, followed by the Duchess Street Mission.

In the years that followed the re-burials and construction, remains continued to be found which constantly pushed the perceived historical boundaries of the burial ground to a larger size. It would seem, that the graveyard was quite extensive in comparison to the Mission’s actually surveyed lot.

Notes

1 John Ross Robertson, Landmarks of Toronto, Vol. IV (Toronto: John Ross Robertson, 1904), p.223.

2 Ibid.

Image Credit:

Detail of Town of York patent plan showing the lots on Duchess Street between George Street and Caroline (later Sherbourne) Street. The burial ground was just above the double “ss” of Duchess. (Archives of Ontario RG1-100 Patent Plans). Thanks to Jane E. MacNamara and her post “Discovering the Duchess Street Burial Ground” on TorontoFamilyHistory.org for this image and information.

41. Dr. Widmer's House

Dr. Widmer’s House

Doctor Christopher Widmer’s (1780-1858) second home in York was a large two-storey, double gabled, red brick house on Palace (now Front) Street(1). It was later painted white and stood about 50 feet back from the road. Widmer’s lane, a narrow path which lead to the house, was the only method to enter by vehicle and created a quiet and private entryway. The building enjoyed a view and splendid isolation until a brick factory was established across from it.

Widmer, of Buckinghamshire, was an army surgeon who came to Canada during the War of 1812(2). After the war he settled in York and was appointed a lifelong member of the Upper Canadian Medical Board. York had been in great need of an organizing body to regulate health care as it had been twice visited by Asiatic Cholera. The Board, established by an Act of Government in 1818, and was responsible for licensing medical practitioners in the province(3).

Widmer also had a key role in the founding of the General Hospital. In 1812 the only hospital in York had been a make-shift one in St. James’ Church. A civilian hospital was required and planning for it began in 1817(4). The York General Hospital (1829-1856) was opened in June 1829(5).

By 1834 there were 15 licensed doctors in Toronto and the hospital had been renamed the Toronto General Hospital(6). It moved in 1856, and the old hospital was demolished in 1862.

Notes

1 Robertson, I, p.200.

2 Firth, p.83.

3 Ibid., p.236.

4 Martyn, Original Toronto, p.61.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

42. The Ruins of the Second Parliament Buildings