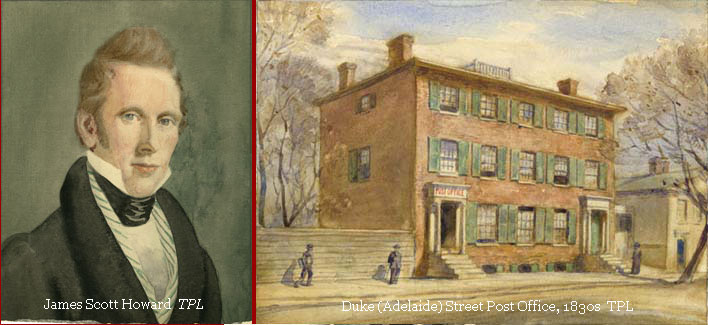

Exhibit: James Scott Howard, Postmaster

Part 1: Howard and Toronto’s First Post Office

James Scott Howard, c.1835, courtesy of the Toronto Public Library

Founding

James Scott Howard was the grandson of one Nicholas Houard, a Huguenot (Protestant) native of Normandy, France. In the late 18th century, during a period of backlash against the French Revolution, militant Catholics began attacking the Protestants who had largely supported it. This was especially true in the south of France and Houard was compelled to leave the country. Having sequestered his family in the Netherlands he made his way to London where they eventually rejoined and continued on to settle at Innishannon in County Cork, Ireland. It was there that he changed the family name to Howard, and there that one of his seven children – John, a son of his second marriage – would marry Mary Scott. The only child of that union, James Scott Howard, was born on September 2, 1798.

York’s Second Post Office

In 1819, young Howard emigrated to Fredericton, New Brunswick, moving to York later in the year where he secured a position as assistant to William Allan who was then Postmaster, Collector of Customs, Inspector of Licences and Treasurer. In June of 1822 Howard married Salome MacLean, originally of Fredericton and the daughter of Archibald MacLean who had served with the British during the American Revolution. The couple would have three children: Prudence Eliza Howard, Archibald John Howard (who died before his fifth birthday) and Allan MacLean Howard.

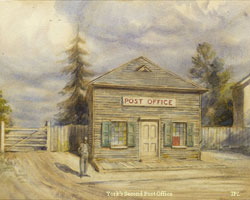

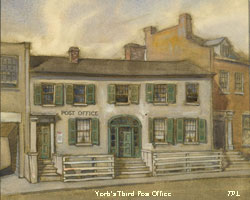

York’s Third Post Office

In July of 1828 James Scott Howard succeeded William Allan to the position of Postmaster which, in a colonial capital at that time, was a political and economic plum. At the start of his tenure the post office operated out of a rented log building on the south side of Duke (Adelaide) Street, between George and New (Jarvis) streets. Within a year Howard had built a new post office and residence on the west side of George Street between Duke and King Streets.

Postal service in Upper and Lower Canada was administered as a department of the British postal service under the supervision of the Postmaster General and the Colonial Secretary in England. The Deputy Postmaster General for British North America, Thomas Stayner, was headquartered at Quebec. As early as 1816 Stayner had suggested to his English superiors that Upper Canada ought to have its own overseer and had recommended William Allan for the position. While this proposal was not formally accepted, the position of Postmaster at York became the unofficial Deputy Postmaster General of Upper Canada. The position that Howard had inherited from Allan, then, made him the most important postal official in the colony and, at one time, the most highly paid.

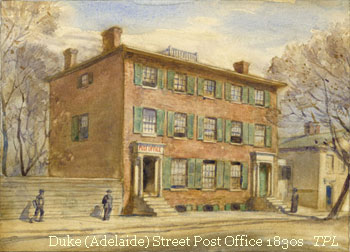

The ever-expanding population of York, which by 1833 had reached 9,000, and the resultant increase in business and staff meant that Howard soon found it necessary to consider a new and larger establishment. As postmaster he was responsible for securing premises, hiring and paying clerks, and purchasing supplies. These costs, in addition to his own salary (substantial at £713 per annum), he deducted from the postal revenue submitted to Stayner in Quebec. He therefore had the financial wherewithal to proceed with his building plans.

In March of 1833 he entered into negotiations with the directors of the Bank of Upper Canada – of which William Allan was then President – for the purchase of a sixty-foot lot, to its full depth of 200 feet, at the eastern end of the bank’s property on Duke Street. On the 27th of that month he received a letter from Thomas G. Ridout, Cashier, which concluded as follows:

…I am directed to say that they have consented to sell you the said sixty feet, commencing from the corner of the lot next to Sir William Campbell’s, for the sum of five hundred pounds.

This bargain is made with the full understanding and perfect confidence of your erecting a reputable brick building, such as the President stated he had seen a plan of at your house, and that it was your intention to erect; and also with the confidence that the Post Office establishment is to be kept in it.

The bank, having lost within the year its monopoly as the only chartered bank in Upper Canada, saw the relocation of the post office on their former property as good for business; it would create a financial centre for the town. The deal was finalized within a month and by October it was noted in the Canadian Current that “Mr. Howard is putting up a handsome house and Office near the Bank.” The new post office opened in December of 1833 and James Scott Howard moved his family (which now included two children, Prudence and Archibald) into the residence on its upper floors.

Duke (Adelaide) Street, 1830’s. York’s Fourth Post Office.

Toronto’s First Post Office, 1830’s

The new premises included a reading room complete with a fireplace and equipped with tables and chairs at which patrons could read their mail and compose letters in response. Such hasty replies were dictated in the 1830s by both the length of time for delivery – a letter to England might take two months to arrive at its destination – and the inconvenience of a trip to the post office from anywhere but right in town. There was no home delivery; every three months Howard was required to publish in the local press a list of those persons for whom mail had arrived and was waiting. He and his staff were available to read and write the letters of those who could do neither.

The Duke Street post office, open eleven hours a day (8 a.m. to 7 p.m.) from Monday to Saturday, was also most likely the scene of a considerable amount of informal socializing. It was also open for one hour (9 a.m. to 10 a.m.) on Sunday mornings, presumably for the convenience of those coming into town for church services. In addition to “general delivery” mail, there were 204 individual post boxes for rent, many of which were taken up by the government, the bank, and the clergy. Members of York’s business community also rented boxes. Newspaper publisher William Lyon Mackenzie had his own box, as did the future Premier of Canada West, Robert Baldwin.

When York incorporated as the city of Toronto on March 6, 1834, its fourth post office became Toronto’s first. William Lyon Mackenzie was Olive Grovethe nascent city’s first mayor, a position which at that time had a tenure of one year. The flow of mail was considerable; the gross amount of letter postage received at the Toronto office that year was £4,365. By 1835 Howard had decided to move his family out to a new home, “Olive Grove,” which he had built on a twelve-acre lot at “Gallows Hill” on Yonge Street just south of the Third Concession (now St. Clair Avenue). Howard himself would make the daily five-mile commute on horseback, and the freed-up space in the Duke Street residence could be used to accommodate the expanding postal operations which now required maintaining a staff of six.

Olive Grove

It was while Howard was engineering this expansion that the newly necessitated position of Post Office Surveyor of Upper Canada was offered first to John Macauley, Postmaster at Kingston, who refused. Stayner then offered the position to Howard saying, “I consider that you possess all the qualifications that are necessary to the office.” Pre-occupied with the construction of a new home and the relocation of his family, Howard, for whatever reasons, also declined. So it was that the position was finally accepted by Charles Albert Berczy, who had been Postmaster at Amherstburg since 1829.

Rebellion, Conflict, and Change

It is necessary at this point to step back from the personal fortunes of James Scott Howard in order to understand the political climate that was then brewing and which would eventually seal his fate as Postmaster of Toronto. The Bank of Upper Canada, Howard’s neighbour and commercial ally, played no little part in the tensions that resulted in the rebellion of 1837.

Bank of Upper Canada, Duke Street

One quarter of the bank’s shares were held by the colonial government and the remainder by a ruling clique – connected by marriage, patronage andBank of Upper Canada conservatism – that came to be known as the “Family Compact.” Shortly after the bank first opened in 1822 (initially at the corner of King and Frederick Streets) its directors had divided into two separate factions. On one side was the Anglican Archdeacon John Strachan and the Boulton, Robinson and Jarvis families. The other, politically moderate side consisted largely of merchants and professionals led by the Baldwin and Ridout families. The former group’s power was vested in the appointed Legislative Council which had both a veto over the elected Assembly (largely reformers) and the ear of the new Lieutenant-Governor, Sir Francis Bond Head. In the 1836 election Bond Head overstepped his authority and intervened in order to secure the return of a “loyal” House of Assembly. At that, the moderate reformers withdrew from active politics and opposition to the government was taken up by the radicals led by William Lyon Mackenzie, publisher of the Colonial Advocate.

The grievances against the government, over which Mackenzie became increasingly outspoken –in his newspaper and in public forums – were both numerous and exacerbated by economic depression. The Bank of Upper Canada, or at least its ruling elite, was seen to be exploiting any available commercial opportunities while little or no money was available to farmers or small businessmen. The farmers, many of them new immigrants of modest means and evangelical religious persuasion, were also resentful of the Clergy Reserves, the one-seventh of the colony’s land held by the Church of England for its own benefit. The church, holding out for higher prices, would not sell although their property often stood inconveniently in the way of a farmer’s expansion or access to water. Furthermore, promised infrastructures such as roads were slow in coming.

William Lyon Mackenzie

Even the postal system – the Royal Mail – was cause for complaint as all profits from the exorbitant letter rates flowed back to Britain and thus did nothing to improve either the service or the fortunes of the colony. Thomas Stayner, the Deputy Postmaster General stationed at Quebec to whom John Scott Howard reported, was the highest paid public official in British North America. Furthermore, he had the power to punish Mackenzie for his radical views by charging him the full letter rate (more than other papers had to pay) on subscriptions to the Colonial Advocate. A committee of the Assembly, set up to examine the postal department – of which Mackenzie was a member – concluded in 1836 that the postal system should be taken over by the legislatures of the Canadas. Its recommendations were not acted upon, however, and postal reform would wait another fifteen years.

Under the circumstances, James Scott Howard took every advantage of his position as a public official to maintain political neutrality. He did not vote in elections, nor did he attend any of the public meetings held with greater frequency as the foment increased. He was cautious in his dealings with Mackenzie and, although required to place quarterly advertisements in the Colonial Advocate notifying its subscribers of mail waiting at the post office, he made a point of obtaining written permission from Stayner on every occasion. When rumours of rebellion and a potential attack on the bank led to the formation of an armed guard, he refused to join up, citing his right to exemption as a postmaster. In the end, Howard’s neutrality would not serve him well with either side of the impending conflict.

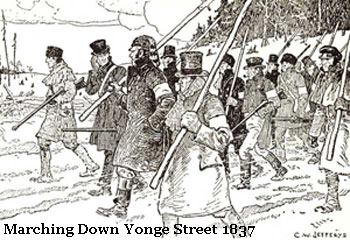

Marching Down Yonge Street, 1837

On the evening of December 4, 1837, while Howard was enjoying the company of his family at home on the 3rd concession, Mackenzie and about five hundred poorly armed rebels were assembling at Montgomery’s Tavern just one concession to the north (later Eglinton Avenue). Word of their plan to march down Yonge Street preceded Howard to town and church bells were sounding the alarm at one o’clock in the morning. By the time he arrived for work the city was in a state of disorderly excitement, the streets crowded with local militia who were largely unprepared for such an attack. The bank guard was patrolling Duke Street in front of both bank and post office and the former had been blockaded with two cannons. To make matters worse, three of Howard’s six employees had not shown up for work.

Who did appear, at around noon, was Charles Albert Berczy, the Post Office Surveyor of Upper Canada, announcing that he planned to stay for a while. Berczy spent the afternoon searching through the mail for anything he deemed “suspicious,” hoping to intercept any correspondence between the rebels. He proceeded to open several of these letters, an action that was likely illegal. When the post office closed in the evening, Howard and his staff took all the mail to the bank for safekeeping. That night, and for several following, both he and Berczy would sleep at the post office.

Howard might not have slept had he known that as Mackenzie made his way down Yonge Street he had knocked on the door of Olive Grove and demanded of Howard’s wife that she prepare a meal for fifty men. She declined, and directed him to the servant in the kitchen. There happened to be a great pot of mutton on the fire which his men emptied and refilled with beef from a barrel in the cellar. They also requisitioned a baking of fresh bread, after which they went out to hone their weapons in the tool house.

After meeting with some emissaries from the city, Mackenzie later returned to the Howard residence and renewed his demand for dinner. When Mrs. Howard did not bestir herself, he shook his horsewhip at her and directed her to the window from which could be seen Dr. Horne’s house, which Mackenzie had set ablaze much to the dismay of his men. It was reputedly Samuel Lount, later to hang for his part in the uprising, who reassured Mrs. Howard that no harm would come to her. The rebels didn’t get much farther that day. Having squandered the advantage of surprise, they were ambushed by a small party of loyalists at a spot near present-day College Street and retreated northward.

While news of this rout was reassuring, tensions remained high and things became no easier for Howard the next day. Yet another of his employees was truant. The volume of mail had increased and once again it had to be hauled to the bank at closing time before Howard and Berczy could bed down in the post office, only to fetch it back on the following morning.

That day – Thursday, December 7 – Howard received a letter addressed to himself from John Lesslie, Postmaster at Dundas. As this correspondence was most unexpected and because he was reminded of the fact that Lesslie had been in business with Mackenzie some years previous, Howard presented the letter to Berczy who opened it. To the surprise of both men, the cover contained a second letter, this one addressed to Lesslie’s son James, of Toronto, from his younger brother Joseph, of Dundas. Berczy proceeded to open this letter too, and upon reading it deemed the content to be of a seditious nature.

Battle at Montgomery’s Tavern

That same evening a large contingent of loyalist troops, including reinforcements from Hamilton, marched up Yonge Street in impressive formation. They engaged Mackenzie and his rebels at Montgomery’s Tavern in a battle that lasted less than half an hour. They then burned the tavern and marched back to Toronto. Mackenzie’s ill-fated rebellion was over and he fled across the border.

At the post office, Friday passed much as the previous two days, without notable incident for the unsuspecting Howard. On Saturday morning, yet another of his clerks –one suffering from an illness that had progressed throughout the week – failed to materialize. At nine o’clock Berczy informed the beleaguered postmaster that he was under suspicion of aiding the rebels by means of his position. Howard, ever one for a paper trail, wrote to Berczy immediately and demanded that an investigation be undertaken to assuage the situation. The following day being Sunday, he took advantage of the post office being open for only one hour to visit his family whom he had not seen in five days.

Charles Albert Berczy

Monday and Tuesday, with a staff reduced to John Ballard, his senior and only remaining clerk, and with the volunteered assistance of Berczy, Howard continued the enormous task of sorting the mail of which there was a considerable backlog. On Wednesday morning, December 13, he received the news that was to alter the course of his life. Just after the post office had opened, a Mr. Joseph who was secretary to Sir Frances Bond Head arrived with a letter informing Howard that “…His Excellency the Lieutenant-Governor has thought proper to remove you from the post office…” His duties were to be taken over by Berczy. Without any formal charges laid against him, without benefit of the investigation he had requested or even so much as an explanation he was relieved of his position after almost eighteen years of exemplary service.

Astonished at this sudden turn of events, Howard set about right away to regain his post. He first contacted his former superior in Quebec, Thomas Stayner Charles Albert Berczywho, but two years earlier, had offered him the Surveyor (or overseer) position that Berczy currently held.Lt Gov Bond Head Stayner referred him back to Bond Head. Since the Lieutenant-Governor was nearing the end of his tenure, Howard merely requested of him that the merits of his case be made available to Bond Head’s successor for judgement. Over the next eighteen months Howard was bounced around from official to official on both sides of the Atlantic.

Sir Francis Bond Head

Having made eloquent pleas for reinstatement to two Lieutenant-Governors, and both the Postmaster General and the Secretary of State for the Colonies in England, he eventually exhausted his avenues of appeal. By the spring of 1839 he took his case to the people and published a pamphlet entitled A Statement of Facts Relative to the Dismissal of James S. Howard, Esq. Late Postmaster of the City of Toronto, U.C. While in the end he was unsuccessful in obtaining either an investigation or a reinstatement, he did succeed in convincing the public that he had in fact been the victim of a miscarriage of justice.

What had been Howard’s crime? The Executive Council had noted of him that, “Mr. Howard in private life was said to associate with persons whose violent course in party politics gave good ground for suspicion of their being connected with the Rebels, or friendly, or a least not adverse to them.” It was suggested that the rebels’ organization had been aided by an extensive correspondence conducted through Her Majesty’s Post Office. Council also implied that Howard had refused to open the mail of suspected rebels, as well he might have, although he maintained that he was never asked to do so. The conclusion was that “although Mr. Howard might have been neutral as regards politics, a man in his situation at least could not be neutral.”

Adversity and Restitution

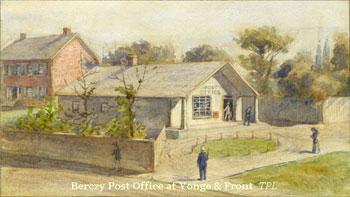

Berczy Post Office at Yonge & Front

While awaiting the outcome of Howard’s appeals, Berczy had maintained postal operations in the building on Duke Street. Howard, in the interim, had no means of support for his family who were still living at Olive Grove while the majority of his resources were tied up in the city property. Once it became clear that Howard would not be reinstated, Berczy moved the post office and his own household to new premises at Yonge and Front Streets, leaving Howard to rent out the vacated building as best he could. Meanwhile, he moved his household first to Trafalgar, near Oakville, and then to Burford, west of Brantford, where he was closer to relatives and could support his family by farming – an occupation to which he was no doubt ill-suited.

Among the temporary occupants of the Duke Street property were Dominique Checkini Ballet 1840 and his wife, ballet dancers who had been touring North America with a French company. They had been performing at the Theatre Royal on King Street until a cholera outbreak forced the group to disband. In rooms they then rented from Howard, the Checkinis offered instruction in quadrilles, mazurkas, gallopades, various waltzes, and fencing.

In 1841 Howard was able to sell the Duke Street post office – at a loss, but his financial need was urgent – to hardware merchant Thomas Denne Harris for a private residence. (Click here to learn of the building’s future fate.) Howard remained in Burford until 1842 when he was, interestingly enough for a man so formerly maligned, named Treasurer of the Home District, the region surrounding and including Toronto. After the reorganization of the counties in 1849, he became Treasurer of the United Counties of York and Peel.

Upstanding citizen that he was, Howard also served on the General Board of Education (1846), became the treasurer of the Irish Relief Fund in 1847, was secretary of the Upper Canada Bible Society from 1846 to 1860 and was treasurer of the Upper Canada Tract Society. Having returned to Toronto in 1842, he remained there until his death in 1866. James Scott Howard is buried in St. James Cemetery.

Image Credits

- James Scott Howard, c.1835, courtesy of the Toronto Public Library

- Fourth York, First Toronto Post Office,

watercolour by Owen Staples, c. 1912?, J. Ross Robertson Collection, courtesy of the Toronto Public Library - York’s Second Post Office,

watercolour by Frederic Victor Poole, J. Ross Robertson Collection, courtesy of the Toronto Public Library - York’s Third Post Office,

watercolour by Frederic Victor Poole, c.1912, after pen and ink drawing by Owen Staples, J. Ross Robertson Collection, courtesy of the Toronto Public Library - Olive Grove, Robertson’s Landmarks of Toronto, Volume I, 1894, p.532

- Bank of Upper Canada, head office c. 1859, photograph by Armstrong Beere and Hime, Toronto, courtesy Toronto Public Library

- Sir Francis Bond Head, detail of an 1837 painting, courtesy of the Toronto Public Library

- William Lyon Mackenzie, detail of

painting , Archives of Ontario - Charles Albert Berczy, detail of

drawing , courtesy of the Toronto Public Library - CW Jefferys’ March Down Yonge Street, December 1837

- The Battle at Montgomery’s Tavern, sketch based on a contemporary English engraving

- Post Office at Yonge and Front, courtesy of the Toronto Public Library