A Biography of John Graves Simcoe

A Portrait of John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe was born 25 February 1752 in Cotterstock, England to Katherine and John Simcoe. He was educated at Oxford and served as an officer with the British army in the American Revolutionary War. He was a successful commander achieving the rank of lieutenant-colonel and was wounded three times before being captured in 1779 and sent back to England. Simcoe’s personal fortunes improved when he married Elizabeth Posthuma Gwillim in 1782. She provided significant financial support for his career, enabling Simcoe to pursue military promotion, purchase a major estate, and eventually enter British Parliament.

On 12 September 1791 Simcoe was commissioned to be the first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada. His long-term goal was to oversee the development of Upper Canada into a model British colony. Simcoe arrived in Newark (today’s Niagara-on-the-Lake) in 1792. Given the possibility of renewed hostilities between Britain and the United States, Simcoe decided to relocate the capital away from the US border. He moved the capital to the Mississauga settlement of Toronto which he renamed York, to honour the Duke of York, son of King George III. This new capital, located on the north shore of Lake Ontario, had an excellent natural harbour and was strategically located away from the border, halfway between the military centres of Niagara and Kingston.

With Britain at war in Europe, Simcoe began to strengthen Upper Canada’s defences. He passed the Militia Act in 1793 creating a provincial militia and requiring that all male inhabitants between the ages of 16 and 60 be available for military service anywhere in Upper Canada during time of war. He additionally established a naval force on the Great Lakes in preparation of a potential American invasion.

York Harbour in 1793.

His next priority was to promote settlement in the new colony. To encourage immigration to Upper Canada, Simcoe established a system by which the government could regulate the distribution of land. Land was granted free of charge if settlers were able to build their property within one year. He envisioned a settlement populated by loyalists and believed in establishing a ruling elite similar to England’s ranked nobility. He ended up granting entire townships to individuals who in turn organized settlements, in effect making them local gentry.

Simcoe additionally focused on his road-building program. Two primary routes were built for strategic purposes: to influence the direction of future settlement and trade, and to help in the defense of the province. Dundas Street, named for the Colonial Secretary Henry Dundas, ran from Burlington Bay to London and later expanded eastward to York. Yonge Street, named after the Minister of War Sir George Yonge, ran north to Holland Landing. Smaller roads where left to local authorities to build and manage.

Simcoe is most remembered for having passed the Act Against Slavery on 9 July 1793. This act ended the sale of slaves in Upper Canada and freed slaves that entered the province from the United States. This legislation was a step in the gradual abolition of slavery. All slaves already in Upper Canada would remain enslaved, their children would be born into slavery but freed when they reached the age of 25, and no new slaves could be brought into the province.

In 1796, due to failing health, Simcoe left York and sailed home to England. Just a few months later, while he was still officially serving as Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, Simcoe was sent to St. Domingue to fight against the slave uprising in the Haitian revolution. Once more he lasted only a few months before resigning due to ill-health and returning to England where he remained until his death in 1806.

Bibliography:

- Williamson, Ronald. Toronto: A Short Illustrated History of its First 12,000 Years. Lorimer Press, 2008.

- http://www.spacing.ca/toronto/2017/09/05/john-graves-simcoes-weird-relationship-slavery/

- http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/simcoe/john.aspx

- https://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/en/pages/our-stories/exhibits/john-graves-simcoe

- http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/simcoe_john_graves_5E.html

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-graves-simcoe

Re-examining Historical Figures

Recently, controversies about commemorations, statues, and historical remembrance have fuelled public debate in Canada. Throughout the country, communities, landmarks, businesses, and streets have been named after historical figures. While some believe that these people should be honoured due to the service they did to our nation, others question this because of those individuals’ actions, attitudes, or beliefs towards particular subjects, and groups of people. As times change, some historical figures may not be universally viewed as positive representatives of Canada. In this light, we are offering a set of questions to help you engage thoughtfully in these conversations:

- Consider whether Canadians should revisit honouring controversial historical figures based on our current understandings. Should the way we value people’s contributions be reconsidered as our views of what is acceptable behaviour change over time?

- Consider multiple perspectives when studying a person’s legacy. Note that perspectives may vary according to culture, geographic location, politics or religion. Ask yourself:

- Why would some people oppose honouring this historical figure?

- Why would some people agree with honouring this historical figure?

- Now grab a pen and brainstorm a list of criteria that you would want to be exemplified by a person after which a public place is named. What qualities and characteristics should this person have?

With this framework in mind, consider John Graves Simcoe. To this day, the name Simcoe can be found throughout Toronto and the province of Ontario in honour of the man who is best known to Canadians as the first lieutenant-governor of the new British colony of Upper Canada. But history is nuanced, as is Simcoe’s legacy. How do you choose to remember Simcoe?

Further reading:

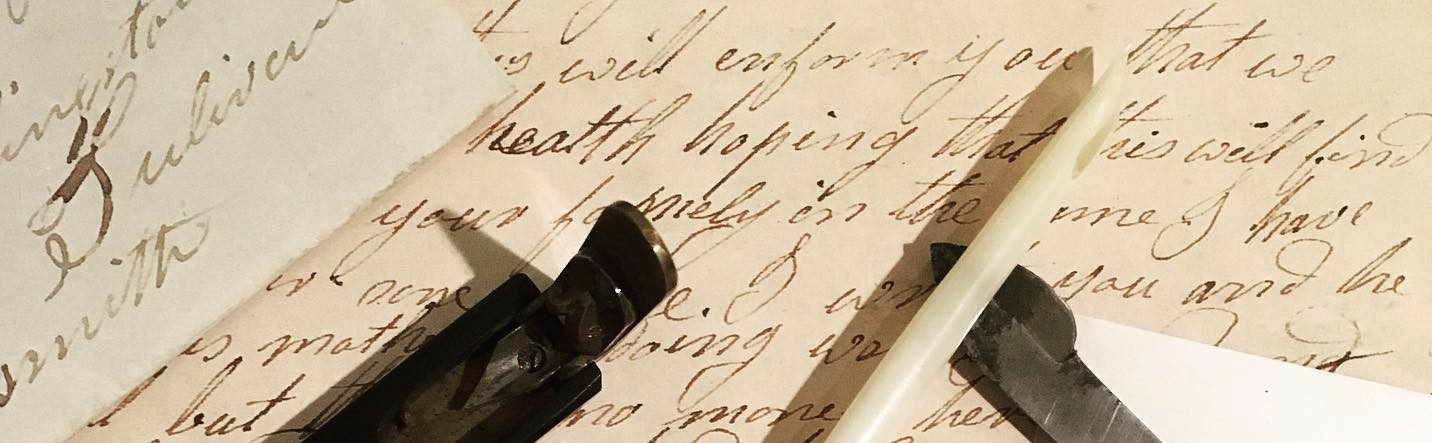

Activity: Dear John Graves Simcoe…

Imagine if you could travel back in time and talk to Simcoe. What would you like him to know about the future of our city?

In this activity we invite you to write a letter to John Graves Simcoe and share what you would want him to know about Toronto today. Use one of the templates below or make your own (Not sure how to write a letter? Check out our tutorial here.) This activity is suited to all ages.

Mail it to: Toronto’s First Post Office, 260 Adelaide St. E, Toronto, ON M5A 1N1

Please note that all letters mailed to Toronto’s First Post Office as part of this campaign become property of the Town of York Historical Society and may be shared for exhibition or educational purposes. Mailing addresses and last names will remain confidential.